Narrator: Robert “Bob” Brewer Norris, age 93

Date of interview: Jan. 19, 2025

Location: Knollwood Life Plan Community

Interviewers: Gardiner Dietrich, age 15, with Mark Auslander

Transcribed from audio recording by: Gardiner Dietrich

Abstract

Robert “Bob” Brewer Norris, a 93-year-old retired lawyer, was the seventh of eight children in a Catholic family in Kalorama in Northwest DC. His father, a doctor, delivered healthcare and babies, increasing the population of the neighborhood. His youth and teenage years were spent as an altar boy, a messboy on a tanker, and eventually the next son in line for the nightly chore of shoveling coal into the family furnace. Childhood memories include playing pinball and patriotic wartime scavenging.

After attending Landon School and graduating from the University of Virginia, Norris joined the Marine Corps before studying law at George Washington University. He clerked for U.S. District Court Judge Matthew McGuire then joined the U.S. Attorney’s office, where he admits to actually enjoying the writing of legal briefs. One notable case he recalls involved a pre-Roe v. Wade abortion prosecution in the 1960s in which the would-be mother was made to testify as a victim against the two defendants who carried out the abortion.

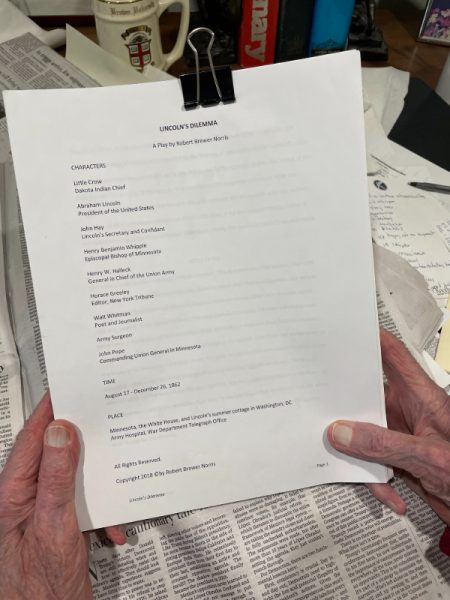

Norris has a deep admiration for Abraham Lincoln and describes himself as a “Lincoln man.” Personally transfixed by the moral quandary the 16th U.S. president experienced while deciding the fate of 303 Dakota natives in the infamous 1862 “Dakota Uprising,” Norris wrote an article for a legal magazine about the incident. On the comment by a friend that the story had the ingredients for a play, he sought the counsel of a university drama teacher and wrote a play called Lincoln’s Dilemma, which speaks to Lincoln’s moral struggle in deciding whether to sign execution orders for the Native Americans, none of whom had fair trials. Norris, who says he never intended to be a playwright, describes his process of writing the play that allowed him to explore the historical conflict more dynamically than merely authoring a book of historical fiction. He is working on getting Lincoln’s Dilemma performed while tackling play number two.

Norris has a daughter, Reid, with his former wife Barbara Jean Lockhart. He spent 30 years with longtime partner Joyce Hoffman Sargent until her passing in 2009. He now lives in Knollwood Life Plan Community, where he is a ubiquitous presence with his silver-white hair and trimmed beard.

Norris traces his family’s connections to various military events. The family’s military history spans multiple generations, with stories of an uncle who died in the command of victorious Buffalo soldiers in Nogales, AZ, to relatives involved in World War II, including his brother, an aviator in the South Pacific.

Although Norris is busy living to his full potential now, he shared how he’d like to be remembered after his death: He simply hopes that he is forgiven by mistakes or slights he might have made in life. Meanwhile, he’s got another play to write.

Gardiner Dietrich:

We are at Knollwood, a senior residential community in Northwest DC, to talk with Robert Norris, a retired lawyer who is 93 years old and has, in the previous decade, become a playwright. Let’s start from your childhood. You grew up in a large Catholic family in Northwest Washington, DC?

Bob Norris:

I was born at the old Georgetown University Hospital then located at 36th and O streets on Dec. 2, 1931, and I grew up in an area called Kalorama. My house was in the 2200 block of R Street, about half a block from Sheridan Circle, named after General Philip Sheridan, a Civil War general. He was very late getting married. He married a very young lady, I think he was about 45 and she was about 20 [laughs].

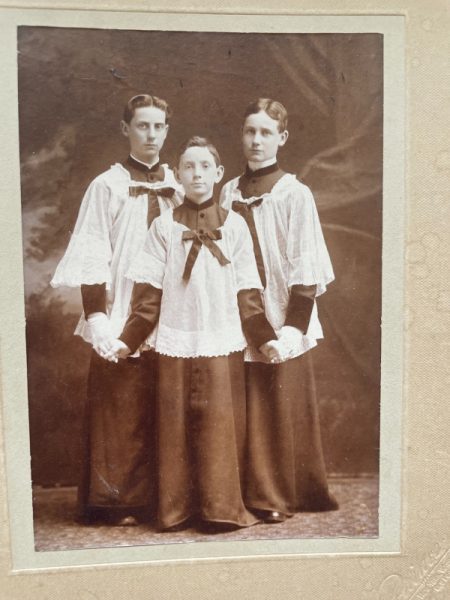

They had, I believe, four children. When that circle was developed with the big statue of Sheridan on a horse, his widow bought a house within eyesight of the circle. And the story is that every morning she would open the window and say, “Hi, Phil!,” or words to that effect [laughs]. I knew two of their daughters; I think they might have been twins. I was an altar boy at St. Matthew’s Cathedral [at 1725 Rhode Island Ave. NW] when the Mass was said in Latin, and I frequently saw them at church.

What was it like growing up there? Have things changed much?

It was a very interesting neighborhood when I think about it, and there were a lot of interesting people. It was three blocks from Connecticut Avenue, which had a lot going on. I remember a drug store called the Empire Drug Store. The entrance was on Connecticut Avenue, but it went all the way through to 21st Street in the rear. In those days, it was all connected. Today it’s two separate entrances, one on Connecticut Avenue and one on 21st. I was there on April 12, 1945, [because] I remember that day.

Somebody had drilled, with a brace and bit, a hole through the wooden hull of the pinball machine. Normally you’d put a nickel in, in those days – I mean, today, it’s whatever, I have no idea. We would shoot this wire through (the drilled hole), and all of a sudden, we’d have ample games. It was – theoretically, we were stealing – well, we all sort of thought it more as a prank than a theft.

Aha.

We were playing with that pinball machine when the Doc – the pharmacist was always called Doc – came over and said, The president is dead. This is Franklin Roosevelt. And I mean, I remember it, you know? I remember it very vividly. We stopped playing the machine. Since I knew nothing about Harry Truman, I thought Henry Wallace would make a better president. What did I know, I was a kid.

What else? We lived across the street from the [Supreme Court] Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes [served from 1930-1941]. The 2100 block was where Franklin Roosevelt lived when he was assistant secretary of the Navy [under President Woodrow Wilson during the outbreak of World War I]. I think that’s where he started his romance with, you know, Lucy Mercer Rutherford [hired by Eleanor Roosevelt as her social secretary in 1914]. That lasted, unbeknownst to Eleanor, right up to the day he died.

I understand you went to a neighborhood Catholic school through sixth grade then went to Landon School before enrolling in the Unviersity of Virgina?

We attended St. Matthews Cathedral. It had a school called Calvert School on Rhode Island Avenue that I attended. Believe it or not, the nuns could inflict corporal punishment in those days, sometimes for practicaqlly nothing. The school went through the eighth grade. I skipped seventh grade and went straight to eighth grade at Landon School. Because Landon was more academically rigorous, I ended up repeating eighth grade and graduated from high school in 1950. I went from there to the University of Virginia and graduated in 1954. I then went into the Marine Corps and thereafter law school at George Washington University.

I love the Marines [but] my family was Navy. My father was a medical officer at the end of the first World War. He had just graduated from Georgetown University Medical School in 1917. He went right into the Navy as a medical officer. He was assigned to the battleship, the USS Minnesota. He used to joke and say, Well, I was involved in the Battle of Yorktown [the last major battle of the American Revolution].” That’s because the battleship would land at Yorktown, then sail up the Chesapeake Bay, turn around, and come back to dock again. He said the full “voyage” was going up and down the bay on the battleship. And then he got out of the Navy. He and my mother got married almost immediately.

Your father was Leo Brison Norris [1892-1955], a family medical doctor?

My father was never called Leo, he was always called Brison. He was named after his father, Brison Norris. Leo – for then-Pope Leo XIII – was added partly at the suggestion of his mother. My father’s specialty was internal medicine and he did everything [including] delivering babies. He also taught at Georgetown Medical School for several years [along] with his practice. He taught practically every subject that you would take [in medical school]. I hope this doesn’t sound braggadocious, but my father was a really smart man. He was the star of his family. He had three brothers – one was a dentist, two were lawyers – but he was the star. They all looked up to him. In fact, my mother, Marion Hungerford Norris [1900-1970], was also the star of her family. Anytime something came up, her siblings would say, We better ask Marion.

You have quite a few siblings I believe?

I’m the seventh of eight. Leo Brison Norris Jr., the oldest, was an aviator in World War II and retired as a Navy Captain. He became a commercial pilot. Mary Theresa Symington – she was always called “Peter,” the origin of this is still a mystery to me – was a secretary in the OSS in 1942 and was stationed in London during the “buzz bomb” period – airplanes loaded with explosives that would ran out of gas and fall to the ground; a terrible weapon. She went to Paris after the liberation and reconnected with [a friend who became her husband]. Next were two sisters, Marion Hungerford Smith and Laura May Grayson. Laura May went to Finch College in Manhattan. Next were Joseph Esten Norris and Charles Walter Norris, who became doctors. Then there was me, and last was Suzanne Shearer Norris Weigert, who went to Bryn Mawr College. My younger sister Shearer and I are the only two siblings still living.

So, wow, a big family! Were you close?

There was a certain degree of friction among my siblings, and it turned out that I was the one who was the go-between. In other words, if my oldest brother had some complaint – if that’s the right word – with one of our sisters, I was, and to some extent, I think I was instrumental in bringing them together a lot. At the time, I wasn’t thinking I was doing that, but looking back on it…

Although my brother Charlie [Charles Walter Norris, 1928-2016] was my closest sibling [in age] we disagreed on practically everything. Looking back on our relationship, Charlie always seemed to be disapproving. I think he disapproved of my choice to attend Landon School, rather than Georgetown Prep where he and our two older brothers had graduated. I always felt Charlie’s personality was too rigid. His adherence to all the tenants of the Catholic Church was unbending. There was no room for disagreement. And I don’t think he was ever even an altar boy! I was an altar boy from the time I was six years old through [sometime] before I went to Landon. And when I went to Landon, that was the end of my altar boy activities.

For example, Charlie absolutely rejected the proposition that abortion is ultimately the choice of the woman. He also supported the church’s condemnation of birth control, asserting that those who practiced it had an “abortion mentality.” Moreover, he never questioned the church’s refusal to even consider ordination of women or an end to mandatory celibacy of priests.

Speaking of religious differences, were you aware of any anti-Catholic prejudice growing up in the District?

No. Brown v. Board of Education was in 1954, and in ’48 the Archbishop of Washington put out the word to Blacks that anybody’s free to come to our parochial schools. I felt good about this. Lots of Black people who were Protestants regarded the parochial schools as a better education for their children. That’s part of the answer. I’ve always been opposed to segregation. Politically, I’m a liberal. I mean, I think the government is here, frankly, to serve people… not vice versa. So you know where my politics are.

I guess that could explain your passion with Abraham Lincoln, about whom you’ve written a play.

I’ve always admired Abraham Lincoln. Like thousands of Americans [I think he] was… our best president. I mean, you probably feel that way. There’s George Washington next, and then probably FDR. But Lincoln was … the best. You’re thinking about a play I wrote [titled “Lincoln’s Dilemma,” copyright 2018]. Have you read it?

I read a couple of scenes.

Oh, well, did you like what you read? Why didn’t you finish it?

I just didn’t have time because I was studying for exams.

People say they’d like to [read it], and I say, well, what you should do is block out about an hour and a half and then you go through the whole thing and you get the dramatic effect of the play. Frankly, I think it’s a very good play, and I’m working on trying to get it produced.

Tell us about it.

It’s obviously a play about Lincoln and his moral dilemma in signing off on death warrants for 303 Indians from the 1862 Dakota Uprising. Here he was, dealing with the Civil War and slavery, but the play opens up with Native Americans. I’m sure that if I ever get it produced, there’ll be people sitting in the audience who will say, What’s going on here? The play was inspired by an event depicted in a Lincoln biography by Harvard professor David [Herbert] Donald, a Lincoln scholar. He came out with his one-volume biography [in 1995] titled, Lincoln – clearly the best biography of him. [From that] I wrote an article published in 2014 in The Washington Lawyer magazine. It’s about the Indian uprising in Minnesota and the fact that 303 Dakota Indians were not only convicted but sentenced to death. The play is about how Lincoln handled that.

A friend of mine read it and called me up and said, You know, you’ve got all this conflict … you’ve got the ingredients for a play. After I hung up, I thought about it, so I went over to Georgetown University, and [asked for] the drama department and they said, Well, we have the Department of Performing Arts. I sat down with an associate professor, and discussed the article with her and gave her a copy. She called me about two weeks later and said, Your friend is right. It’s got the ingredients for a play. And then she suggested I enroll in a course at Georgetown.

I wrote roughly five or six scenes while I was taking the course. But everything changes. If you ever sit down to write a play, you’ll be making changes all the time. In fact, when a play opens, just after two or three rehearsals, there are changes. It’s basically the same story, but I made lots of changes. Someone suggested to me that I get the play copyrighted, saying “it’s a pretty amazing idea for a play.” That had not occurred to me until that day. Well, if you get something copyrighted, it only costs about 50 bucks. You do it online. It’s very simple and then about six months later, you send in a hard copy. The play is then protected. You don’t need a copyright, but the copyright strengthens any kind of dispute.

What, exactly, was Lincoln’s “dilemma?”

Early on, you’re given the impression that [Lincoln] didn’t think much about Native Americans, or Indians as they were called then. The Anglo Saxons who came here treated them very badly. By the end of the play, Lincoln is… he’s helped along by Horace Greeley, who’s a character in the play, and Walt Whitman, another character in the play. [By the end of the play] Lincoln’s attitude towards Native Americans changed enormously, and that’s to some extent, well – I think it’s why the play has some relevance to what’s going on right now. That’s a sales pitch! [laughs]. Lincoln’s resolution to the problem – this is the question I want people to ask: Was it correct or not? I mean, he let 38 [people be executed] and pardoned 265.

Another character in the play, Whipple, was the Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota. He had a huge influence on Lincoln. And at the end, he says, “You know, it’s great that you’ve let 265 live, but the ones that have been sentenced to death didn’t get a fair trial.” And that, by the way, is exactly how Native Americans feel about that today, that those people were denied a fair trial. And of course, they were.

So why did you choose to write a play and not a history book?

If you’re writing history, you’ve got to stick with the facts. [A play allows one] to write about all the conflict between characters. In other words, I was not a playwright, but I think I immediately grasped what [my friend] was saying about the ingredients for a play. The professor reinforced the thought of trying to write a play. By the way [laughs], I’m working on another play right now, which is very different and a much more challenging play.

Is it also historical?

Have you ever heard of a journalist named Agnes Smedley? This play is to a large extent based on her life. She was an activist journalist… and I’ve got this play set up so that her life (story) is developed from scenes within the play involving people like Emma Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Joseph Goebbels. I mean, [laughs], it’s all over the place! And then, at the end, she’s interrogated by Roy Cohn. You can imagine that scene!

Do you have a title yet?

Agnes Smedley wrote a book – a novel, but really it’s an autobiography – called Daughter of Earth, and I thought that would be an appropriate title.

Let’s back up to hear about your career path. After college you joined the Marines before going to law school.

I was in a program in college called Platoon Leaders Class that made you a second lietenant upon graduation. And so I joined the Marine Corps after graduating from Virginia. I was in for close to three years. After that I went to [George Washington University] Law School.

Is that also when you got married?

I married Barbara Jean “BJ” Lockhart in 1959. We first lived on 31st Street below M Street below the canal, when I was clerking for the judge. We were married for sixteen years, until the mid 1970s, and had one daughter, Barbara Reid Norris. She was born in 1962. She now lives in Annapolis, and her husband, unhappily, got one of those horrible, aggressive cancers. My son-in-law [Charlie Buckley] was a very successful real estate broker who did very, very well. Charlie was a wonderful father and husband and later, my daughter continued his [business]. And now one of her daughters – one of my granddaughters – has joined her. So the two of them are now doing this work together. The other granddaughter is getting a Ph.D from the University of Chicago in June.

Where else did you live before you moved to Knollwood. And did you ever remarry?

We lived on 34th Street near the Cathedral when my daughter went to Beauvoir School and then National Cathedral School. After the divorce, I moved to an apartment on Cathedral Avenue. I was there until I met Joyce. I called her my wife, but she was my partner for 30 years, a long time. Joyce Hoffman Sargent [1933-2009]. When we met she was a widow. She was a very successful real estate broker. She died of heart disease in 2009.

Before we get too far ahead, let’s go back to your career. I understand you were an Assistant U.S. Attorney in DC for many years. And that you actually enjoyed writing, like, legal briefs.

Most lawyers do not like to write briefs. [But] I’m one of those weird guys. When you read a case, there’s always a factual basis in the case. And I always found a lot of these very interesting, especially criminal cases. My first job out of law school I clerked for a year for U.S. District Court Judge Matthew McGuire. It was one of the best jobs! Then I went to the U.S. Attorney’s office for seven or eight years. I tried a variety of cases before juries, both criminal and civil.

We had one abortion case. At that time – in the 1960s – it was hard to get an abortion because it was against the law, a criminal offense. But the statute was written so that the woman who sought the abortion was considered the victim. As a result, she couldn’t take the ffth and so she had to testify. It involved these two back-alley [abortion providers]. The woman got an infection, was near death, and went into the hospital. She identified the two men and they were arrested and prosecuted. She recovered. She was, of course, the one who sought the abortion, but the statute regarded her as the one who was victimized. If it wasn’t written that way, everybody would take the fifth. These cases were very rare. Looking back, in those eight years, I don’t think I ever heard of another one. Mr. [President Donald] Trump talks about punishing women, but it would result in no trials because everybody would take the fifth.

I loved the U.S. Attorney’s office – that was excitement and fun. I also did quite a bit of appellate work and [was sought after] for writing appellate briefs for the U.S. Circuit Court in DC But I had the idea of going into private practice and I formed a partnership. After a couple of years the Attorney General of the Virgin Islands called me and invited me to be the Deputy Attorney General in St. Thomas and St. Croix. It sounded pretty good to me.

But I couldn’t convince my wife to move to the Virgin Islands. [Instead] I went to work for the National Consumer Finance Association, a trade association, for six or seven years. I testified several times on the Hill, wrote articles and testimony for witnesses. My title was legislative director and general counsel. During that time I divorced. Later, I met Joyce.

How about other memories of your childhood?

Something that I don’t think people in Washington are aware of, maybe you aren’t either… and that is that in 1940, in practically everybody’s house, the fuel was coal.

The boys [in my family] had to stoke the coal furnace every day. That’s what we, and most people, had in our house for heat – anthracite coal. It was delivered as small chips and would be funnelled into the coal room in the basement. And then we would fill a hopper with coal every day in the winter. An auger would carry the coal to the flames. So when the temperature dropped, the auger would turn on and start dumping the fresh coal. This was a great big furnace.

I took over from the brother before me, and I had that job for about four years. Every night about 10 o’clock I would fill the hopper with enough coal to make sure that it would feed the fire all day. Then I would shovel out the ashes into large metal containers and I would take them out to the alley behind the house. Because there was so much dust and dirt, I had to take a shower before I went to bed.

Once a week the ash truck came. I would watch these guys – one was up there catching the metal containers and dumping the ashes and of course, there’s dust going all over the place. It was a totally open truck. I guess the guy must have been standing on some kind of a platform because it was fairly deep – I would estimate that the height of that box was maybe eight feet. I don’t know what they did with the ashes. I guess they dumped them somewhere.

When I left to go to the University of Virginia my dad had this huge furnace removed, and he put in a gas furnace that wasn’t any bigger than a large trunk to heat the whole house. And shortly after that, nobody’s burning coal. The whole city had been heated by coal – much of it would arrive on the C&O Canal. A train track would bring the coal up by 27th Street.

To the old power plant?

That’s right.

Now, you know, that’s fascinating. What a great piece of Washington history.

I thought that was something that might be interesting. That was how houses were heated in the winter. And by the way, we didn’t have air conditioning. My father installed a big fan on the roof of our house, and [when] you opened your window this fan would suck in. So it was a breeze – it didn’t make it any cooler – but a slight breeze was something,

Were winters more severe when you were younger?

No, I think they were milder. I kind of looked forward to snow. I made a fair amount of money shoveling people’s sidewalks.

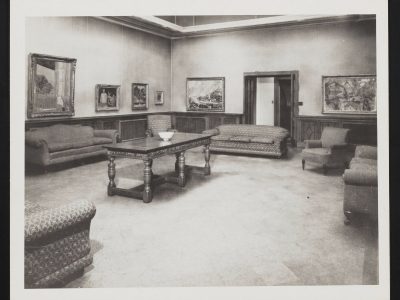

The Phillips Gallery is pretty close to where you lived, right?

That’s another story. I used to go to the Phillips Gallery all the time, and I remember when people were allowed to smoke cigarettes. Can you believe that? And people say, what? And I said, it’s true. The only admonition was, please don’t drop cigarettes on the floor and stamp it out. And so the house – this was before, when it was still just the house – had ashtrays everywhere. I used to go over there. When I was 16 I had a girlfriend, and that’s where we would go to smooch [laughs]. There was a big room that at one time had two Van Goghs, plus a lot of other paintings. I just remember smoking in front of those paintings.

I smoked from [age] 15 but it’s been close to 50 years since I’ve had a cigarette. I wouldn’t be here if I’d kept smoking. I was a very heavy smoker, two or three packs a day.

Kissing in the Phillips, that’s pretty exciting.

Smooching.

A year ago, I ran into a former girlfriend’s sister. She said she’d talked to her sister recently and she’d mentioned that I had introduced her to art. I said, oh, and I kept thinking, ooh, and all I remember was the smooching [laughs]! Well that was about 70 years ago. Yeah, I did take her to museums. I loved going to them.

Other memories of teenage years?

Did I mention to you that when I was 16, I worked on an oil tanker in the summer. My father knew the commandant of the Coast Guard. And the Coast Guard was responsible for issuing papers, ordinary merchant seamen papers, and so I became an ordinary seaman. I Googled this recently – it did start at 16. So when I was 16 years old, I worked on an oil tanker and made three trips from Marcus Hook, PA. It’s near Chester, PA, on the Delaware River. We went to either Port Arthur or Beaumont [in Texas]. We would go down to Texas empty, so we were high in the water. Then when we came back, we were loaded, and I made three trips. I remember when coming back, low in the water, we would catch flying fish. The main cook and I would stretch this net-like material and they’d fly into it. They were delicious. It was a week down and a week back. So I was on that tanker about six weeks altogether. That was a very interesting experience.

This was a Sun Oil Company (Sunoco) tanker. The Pennsylvania Sun was the name of the tanker. It was non-union; otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to work there. I was what is known as the “saloon mess.” In other words, I was the mess boy for the officers on that tanker. You had the skipper, and then first, second, and third mate, and then first engineer, and maybe one or two others, and a purser.

But I do remember the ordinary seamen. Most of their job was chipping and painting. There was constant maintenance of these ships, otherwise they wouldn’t last. That particular tanker incidentally was torpedoed in the Gulf of Mexico, fairly near Key West [on July 15, 1942] by a German U-boat. These U-boats came from Germany or France. They would go all the way down across the Atlantic Ocean to our coast. And they torpedoed lots of ships on our coast, and this particular one got all the way into the Gulf of Mexico. The tanker that I was on had been torpedoed, severely damaged, but repaired and sent back in the service. I became pretty good friends with the purser who showed me various places on the tanker that you could see where the repairs were made.

When you were 16 and working on the tanker, you didn’t know you were going to go into the military yet, did you?

Oh, actually, to be honest with you, I realized that I did not like sailing around on a ship. I was at Landon [and] I took my books, my summer reading, with me and I remember a lot of them – Madame Bovary, The Red and the Black, Buddenbrooks. Buddenbrooks was extraordinary – have you read it yet? No? You’ll like it, or if you don’t like it, there’s something wrong!

You must have been the only ordinary seaman who was reading books like that.

Well, I was just, like, I was a mess boy. But I mingled with the seamen. They didn’t treat me like I was… well, I will say this … I think I showed up there the morning I was supposed to report in a seersucker suit [laughs].

At the end of the final [trip], we arrived at Marcus Hook, which is where the refinery Sun Oil Company was. In those days, they brought crude oil to the east. They didn’t have pipelines, and they would bring these tankers full of oil, and then they would be discharged, and then the refinery would, I guess, turn the oil into gasoline or whatever. As we arrived, there were other tankers ahead of us, so we had to wait in the Delaware River. And while we waited, a freighter came down and crashed into the side of our tanker. And I remember, I was in my bunk, and I don’t think I was thrown out, but I mean, I felt the jar, and everybody felt the jar [laughs]. And of course, I suppose some of those people might have thought, Good God, we’ve been torpedoed. I have a photograph from the Philadelphia Inquirer showing this huge freighter. See, we were low in the water because of all the oil, and this thing was huge, and anyway, I jumped out [of my bunk], and everybody headed for the poop deck, which is where you would get out if you had to abandon ship. That was where we were congregating, and here’s this huge ship, it was like a monster over us. I would guess it took three or four hours before they were able to separate them. But the tanker dumped a lot of oil into the river from the puncture.

It would be interesting to see that newspaper article.

I have it actually. My daughter had a friend at National Cathedral School who had some connection with The Philadelphia Inquirer, and sure enough, she was able to dig up some articles, including a photograph.

Nobody on board was hurt?

No, no one was hurt. It struck fairly close to the stern. Had it been another 25 feet closer, it would have been a serious problem. There would have been fatalities, and the engine room would have been flooded. And you know, it would have been a real mess. The tanker was not all one big thing of oil. It had various compartments so that if you had this problem, you didn’t lose everything.

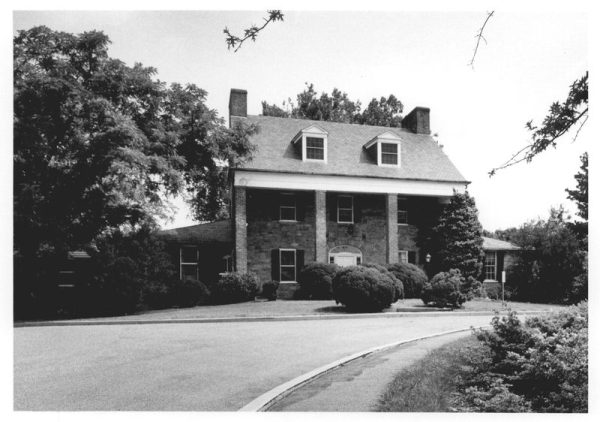

Let’s switch to a topic about some historical research I’ve done that you actually have some connection to. I go to Sidwell Friends School and there’s this house on the property called Zartman House now, but it used to be called The Highlands [built 1817-1827]. It was built by a man named Charles Nourse who raised his family there but also had enslaved people. I’ve been doing historical research on the plantation and the people who owned the land after the Nourse family.

Well, you know who lived there later was [Rear] Admiral [Cary T.] Grayson [1878-1938] Did you see that in your research? He was [President Woodrow] Wilson’s doctor, and part of the cover-up [obscuring the severity of Wilson’s October 1919 stroke], but he was also FDR’s doctor [as well as doctor to presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft]. His son, Gordon Grayson, was my brother-in-law, and he told me that when they lived in that house – they were all horse people – they rode horses up and down Wisconsin Avenue. Really!

He married your sister, Laura?

That’s right. Oh, did I tell you this, or did you, is it part of your research? You looked it up! Yeah, Laura, that’s exactly right [laughs]. Gordon, he was a fabulous person, really. His father was an MD but he would always be referred to as “Admiral” Grayson. There were three boys in that family, Gordon – Gordon was Navy – as was William, and the third boy, Cary, was in the Marine Corps. When you look at that house from the street, it doesn’t look that big, but it is a pretty big house. It spreads out and goes back. I don’t know where the stable was, but I think they had a stable down in the back.

Did Gordon Grayson go to Landon or St. Albans?

He went to St Albans, close enough to walk, or I guess ride. When I first went to Landon in 1945, the headmaster had a horse, and they had a barn and there was a horse paddock. He was still riding and jumping and all that sort of stuff. Well, if you research the Graysons, I’d be very interested. I mean, there’s George Grayson, William’s son, who I know. The family has a horse breeding farm in Upperville, VA, and George is running it now.

Going back to the Nourse’s family: Joseph Nourse [1754-1841] was the first registrar of the Department of Treasury and had worked for George Washington then got a job setting up the Treasury Department. The Highlands was likely built by his son, Charles Nourse. I found so many interesting things. At the Pennsylvania Historical Society I found correspondence concerning the whole question of whether or not Black people could serve in the military – this was during the War of 1812. A letter Charles Nourse wrote to Daniel Parker, adjutant and inspector general of the War Department from 1814 to 1821, was writen on July 9, 1820. Charles was recounting a general who was saying if it doesn’t work out, probably, if they lost, then they could just, like, sell the soldiers who were enslaved. The Army was extremely racist in that period.

I had an uncle [Joseph Dent Hungerford, 1894-1918], my mother’s older brother, who was in the Army. He was a captain in 1918, and there was a border incident at Nogales [Arizona, on the Mexican border], and he was killed. And I remember my mother telling me that she was 18 at the time. She was born in 1900 and they were in a carriage going to church on a Sunday, and coming down this road was an Army officer, and he said, “Can you point out the Hungerford farm?” He was bringing the news. That is how they alerted people, if they could. My mother said, “I remember that so distinctly because we were on our way to church on a Sunday morning.”

In that battle, the troops were Black and the officers were white. When he was killed, he was the commanding officer for Troop C, 10th Calvary. I believe he was leading the attack up the hill across the Mexican border. The man who took control was a second lieutenant who was also very badly wounded and couldn’t continue the attack. So the person that took charge of the company was a Black sergeant, and they did drive out the Mexicans. They were the Buffalo Soldiers.

What a difference 100 years makes. Tell us more about the wars during yours and your family’s lifetimes.

Before we moved to R Street, my parents had a big corner house at 18th and Park Road in Mount Pleasant. A neighbor, Jack Corbett, was a Marine officer. He was killed at Guadalcanal. I hadn’t thought of that. Also, one of my sisters was unofficially engaged to a guy named Hank Gibbons. Hank was in the Army and served in the India-Burma theater. He was on a plane and the plane didn’t make it. I remember when he was declared missing in action. And I remember my sister being quite devastated by this. I’m pretty sure they would have gotten married. My oldest brother was an aviator in the South Pacific on a carrier. Another brother was in medical school when the war ended. So he never saw combat.

Do you recall stories you heard from your eldest brother about the Pacific campaign?

Let me give you some advice. Jot this down: Have the conversations on the things you would like to talk to your family about [because you will wish you had when they are gone]. For example, I mentioned that my father delivered babies. Well, one of the neighbors, when we were at 18th and Park, was the McNamara family. And around [the year] 2000, I was reading the paper one morning, and I saw this obituary. I thought, My God, well, she was about 102 years old. And there was going to be a Mass at Little Flower Church with a reception after it. So I said Joyce, I’ve got to go to this. I vaguely knew some of the children. Ann Tierney was the daughter of Mrs. McNamara, and I walked up to her and said, Hi, I’m Bob Norris. And she said, Oh, Bobby Norris. I remember your father died on March 29, 1955.

I mean, you know, obviously my father was not president of the United States! And then said, See that young woman over there – a woman probably in her 40s – Your father delivered her on the morning of March 29, 1955. That’s my daughter. Your father died that afternoon.

And when word got out that I’m there, it turned out that something like 37 people in that house had been delivered by my father! My father was their favorite, and he wasn’t a gynecologist. In internal medicine he did everything [laughs].

Had you been aware that your father was working on the very last day of his life?

I knew that he was still practicing medicine. I was actually [on active duty] at Quantico [Marine Corps Base] when he died. I got a message to come home like, “Something’s come up. You should come home.” I had a car and I went home, and that’s when I learned. He had a massive coronary heart attack.

Is he buried in Arlington Cemetery?

He is, with my mother and two of my brothers and their wives, and I have a slot, but there’s an issue as to whether or not I will get the slot, even though it’s still in my name. The burial site is located about 150 yards on the left from the McClellan Gate. And the reason for that is I didn’t put 20 years in [active duty military] or receive a reasonably high combat metal, like a Silver Star.

So there’s that issue. By the way, once a slot has been assigned to someone, there’s nothing that can change that until the person dies and they make a decision on whether or not the deceased remains eligible to be buried there. I know because I once offered [my slot] to the husband of my former wife, a highly decorated Marine officer in Korea. We went over there to inquire and they told me, It’s in your name, and it’ll be in your name till you die. Nothing will happen until after you die. I mean, it’s just – at 93, I mean – I’m getting there [laughs]! Bizarre, right? It didn’t work out anyway because he died – and I’m still alive.

Photo by Cate Atkinson

Now I’m told, by a couple of people, that my daughter can make a very compelling case for me, since my family is there. I also have two additional family members on my mother’s side buried at Arlington. Well, I’m not going to take up much room anyway because I’m going to be cremated [laughs].

How would you like to be remembered?

I belong to a church, Christ Church in Georgetown. And I’ve told my daughter I don’t want a bunch of people getting up and saying, “What a great guy.” I’ve been to too many funerals where people get up, and I’m wondering if they’re talking about the same person. And people go on and on and on. In some cases, I’m sure it’s justified, but there are other times…

I think I would just like for the priest to say that he had talked to me, and that if I’ve hurt anybody, I’m sincerely sorry. And that’s all. I don’t want to be remembered as a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright – assuming you know if I get a Pulitzer Prize. Well, yeah, I guess I would like that, a Pulitzer, yeah [laughs].

END

© Copyright Historic Chevy Chase DC

Oral history interviews may be copied for personal, research and/or educational purposes only under the fair use provisions of US Copyright Law. Oral histories accessed through this web site are the property of Historic Chevy Chase DC. the copyright owner.

Use of these interviews is subject to the following terms and conditions:

- Material may not be used for commercial purposes. Short quotes and references are permitted for instructional and publication purposes.

- Users must provide complete citation referencing the speaker, the interviewer, the date and website with URL address.

- Users may not re-post or link the oral history site or any parts of it to another program or listing without permission.

Questions about the use of these oral history materials and requests for permission should be directed to hccdc@comcast.net or HCCDC, PO Box 6292, Washington, D.C. 20015-0292.