Narrator: Gordon Stewart Brown, age 88

Date of interview: Jan. 12, 2025

Location: Mr. Brown’s apartment at Ingleside at Rock Creek

Interviewers: Natalia Weinstein, age 15, with Carl Lankowski

Transcribed from audio recording by: Natalia Weinstein

Abstract

Ambassador Gordon Brown, a 35-year career U.S. Foreign Service diplomat with postings largely in the Middle East, has done more in retirement than most people do in a lifetime – from writing books to serving as chairman of the board at Habitat for Humanity.

Born in 1936 into a family whose social and professional circles revolved around international journalists and political dialogue, Brown was raised bicoastally, in Washington, DC, and San Francisco. His early memories on N Street in Georgetown included hanging out at the corner pharmacy with friends getting root beers and collecting papers for the war effort. At 9, immediately after World War II ended, his family relocated to Rome, then in a post-war devastated state, where he recalls freely roaming the city’s empty streets on a bicycle and collecting postage stamps.

High school passed happily in San Francisco and then he went off to Stanford University, a place he said was hardly the academic bastion it is today. Youthful disinterest in mideaval history led him to drop his dual major, leaving him with a political science degree – a fact he ruefully recalls since the first book he wrote upon retirement was about the medieval period. He took the Foreign Service exam as a junior in college not expecting victory, but it won him an interview with a promise to join the State Department after allowing him a few years to mature in the Army.

Over the years he married, had three children, raised them overseas – Baghdad, Cairo, Tunisia, Saudia Arabia were some of his assignments – and always returned stateside to his home on 32nd Street in Chevy Chase DC that he bought in 1964. His retirement years were enriched by that long-standing neighborhood community, and he busied himself writing five books, volunteering at the Smithsonian American History Museum, attending the theater, teaching elder adults, and passionately advancing homeownership opportunities with Habitat for Humanity, where he served as chairman of the board for three years. He and his wife, Olivia, moved to Ingleside at Rock Creek in 2020.

His advice for a well-lived life: Keep your eyes and ears open to every kind of experience.

I’m Natalia Weinstein and I’m sitting here with Ambassador Gordon Brown. Let’s start at the beginning. You were born in Rome, Italy?

That’s correct.

What date?

Feb. 24, 1936.

Who were your parents?

My father, George Stewart Brown [1906-1957], was from Buckeye, AZ, and my mother, Helen Meyer Brown Lombardi [1908-2000], was from Cincinnati, Ohio. My older sister, Ronny Brown Baxter, was born in ’34 in Vienna, I think, when my father was the Vienna bureau chief for United Press International. She died seven or eight years ago.

Do you remember anything from living in Rome?

You know, once you are older than 20, you have childhood memories that you probably don’t really remember, but there are pictures, family photos and things like that, and then you think you remember them. I do have recollections. I was three when I left, so I probably don’t have any real memories. We lived in an apartment, in a tall building, and that’s about all I remember as a kid.

When did you move to the United States?

We left Rome in the summer of ’39, which would have been just before [World War II] started. We [sailed] back on the SS Rex I remember, which is a great Italian liner, their prime liner. Not that I remember that, but I remember that’s what we came on, which subsequently was bombed during the war, so I never saw the ship as an adult. And we moved to Washington because my father had been recruited – very fortuitously, the timing worked out – to join the American Red Cross.

What do you remember from your early years in DC?

I remember when we lived on Dumbarton Street in Georgetown for a while, and then we moved to our house in Georgetown – our permanent house – on N Street.

What was it like growing up in Georgetown?

I was a school kid. I remember my school, I remember all the things that happened there. We lived there until I suppose I was almost in junior high. I graduated from Jackson Elementary up on R Street, which is now an art collective, I guess. And, you know, I remember my friends. I can instantly remember their names and our escapades around the neighborhood. It was a very middle class neighborhood at that point.

Did you have a favorite school subject?

I think I liked everything. It was an interesting school. There were only four classrooms in six years of studying. So, each class was divided for a year and a half. First [grade] through halfway through second. Second [grade] through halfway through fourth, and so on. We all knew each other. We walked home after school and played in each other’s gardens, threw rocks at cars, and stuff like that. Snowballs at cars, not rocks [laughs].

What about after-school activities?

No, not that I remember. It was a grade school, and they weren’t big on after-school activities. We just played around. What’s the name of the pharmacy on P and 30th streets [Morgan’s Pharmacy], which is still there? We used to stop there for root beers on the way home from school. Anyway, little things like that I remember, but not very much. It was the war years, and I remember collecting paper, and smashing tin cans and taking them to, I guess it was the Little Tavern that sold dime hamburgers at the time, but they were also the collecting point for fat. We were collecting fat for the war effort. And papers for the war effort. We’d take our little red wagons and go around and collect peoples’ papers. We’d take it down to – well it used to be a junkyard, then became Dean & DeLuca on M street in Georgetown. And it’s now just become another upscale restaurant. So it’s still the old building of the junkyard in my mind.

What political issues do you recall about that era?

I mean, we sang silly ditties making fun of the Germans and Japanese. And we bought saving stamps – and I can’t remember what they were called – Liberty bonds, that’s what. We bought the stamps to fill our book, and if I remember correctly, the school had been trying to buy a Jeep. I think it took us a whole year to buy a Jeep. Maybe we bought a Jeep a year, I can’t remember. But I remember there was a big chart in the front hall of the school where they would show how much of the Jeep we owned that week.

What was your dad doing for the Red Cross?

Like any other dad he went to work. And I didn’t know what his work really was, and I didn’t much care. I do remember one of the problems of living in Georgetown at the time, or in any place, was gasoline rationing. My father and mother loved to take picnics on weekends, and they would save the few gallons of gas they had in the car tank to go on weekend picnics. I remember my dad mainly on weekends because he wasn’t around much. He worked long hours, and my mother worked too during the war. She worked for what eventually became the CIA. She was translating, she wasn’t doing anything fancy. She was just translating because she spoke very good German.

So you felt the effects of the war.

We knew about the war, and as I said we had these silly songs that we sang about, you know, “Mussolini is a meany” and “the Japs are worse” and some worse stuff. And we did the collections and stuff. We were very aware of the war because a lot of people had relatives fighting in it, but not my family. My dad went overseas again in early ‘45, because he had been recruited by the Army to go back to Italy. Because having been a press guy before the war, he knew all of the people they wanted to reach in the press and in the media, and so on, and in the arts and what not. He was a public relations advisor to the U.S. Army through Italy. And we joined him in ‘45, just after the war was over in Europe. It was the peace in ‘45, and we were there by July. My sister, my mother and I went out, and set up house in Italy for a year.

How old were you then?

About 9 or 10.

What was post-war life like in Italy? I assume you remember more since you were older then.

Oh yeah, I definitely remember that. We first lived in a house in the outskirts of Rome in an apartment building that they put up, where there was a little farm actually below us.It sort of was an empty lot. And we were up on the third, fourth, or fifth floor, I can’t remember. But there was a family below, and they had kids our age. So we got to know these little Italian kids, but soon after that we moved. We were put in, actually, the ambassador’s residence, which had been used as a rehabilitation or rest hospital for military people during the war. It was in pretty ramshackle condition, but we lived there for the next year. Yeah, I remember Rome. There was no traffic in Rome then, other than military traffic. I had a bicycle. I could bicycle anywhere I wanted to, because the ambassador’s home was not far from the top of the Corso, which is where the embassy was. So we were close to town, close to the Spanish Steps and everything like that. I was collecting stamps in those days, and I knew where all the stamp dealers were, and I would bicycle around them to see if there was any news. I knew my way around downtown Rome pretty well, because a 12-year-old kid with a bicycle in Rome with no traffic? Terrific.

Did you speak Italian?

I learned some. I couldn’t speak Italian. But I could get along.

How many years did you live in Italy?

Well, I think it was close to a year and a half.

And then you moved to California?

No, we came back to Washington for a year, or a year and a half. I can’t remember whether I went back to Jackson [Elementary School] or not. But anyway, it was time to go to high school or junior high, and my parents didn’t like the junior high. It’s the one over on Wisconsin Avenue, it’s still there. So I went to St. Albans. I didn’t like St. Albans. I was very glad when my father got a job in California. So we moved to California, I think we were back in DC maybe only a year or so.

What was it like moving to California? I assume if you didn’t like St. Albans, then you were okay leaving DC?

Yeah, I sort of lost contact with my friends from school days. Particularly when I went to St. Albans. It was a whole different crowd of people, and it was a tough transition, so I was happy enough to leave, yeah.

You settled in San Francisco. How did you like living there?

It was great, it’s a great town. We had a nice house. I went to a good school, good high school, good college. All in the Bay Area.

Were political issues different in San Francisco than in DC?

There were a lot of local political issues. Not too many national ones that I was aware of at the time. I wasn’t very political, I don’t think, at the time. Well, by the time you’re in high school, you’re generally into some sort of sport. Since I wasn’t good at team sports, I was generally in track and cross country.

Your move to California was for your dad’s work?

Yeah, my dad was working for the government when we came back to Washington, DC. He was with USIA [United States Information Agency], which at that point was part of the State Department. And the government had a [salary] cap or ceiling, and it was the beginning of the McCarthy days. He just wasn’t very comfortable in that situation. He then got a good job offer, once again in public relations, from Chevron Oil Company out in California. And frankly, my parents, I think they needed to do it for money purposes, because all their savings had been in British banks. And so, when the British pound was devalued — you probably don’t know this — the British pound used to be in the place where the dollar is now. Anyone who wanted to save money put it in a British bank before the Second World War. After the war, the British pound was worth about 20 percent of what it was worth before because they had spent all of their money fighting the war. And my parents didn’t have any savings left. So they were thinking of sending us to college obviously, so he needed to go to work for a company that paid more than the State Department did. It was quite simple.

You and your sister went to Stanford University?

Yes, both of us. Stanford at that time was just a local college. It wasn’t the great college it became later. Wallace Sterling [1906-1985] was the president of the college at the time, and he was spending money to improve the professional schools – law, medicine, engineering. There’s probably one I missed there. That’s where the money was going. And I was in general studies. I was in history, political science, and that kind of stuff. The money wasn’t being spent on my faculty, let me put it that way. I didn’t think I had good professors. It was just another college, it wasn’t that great.

Was Stanford the only school you applied to?

I don’t remember. To be perfectly honest, 60 years ago, the application process wasn’t quite the gut wrenching issue it is now. I probably applied to someplace else, but I remember not having any real thought about it. They accepted me; I went.

Had your parents gone to college?

My father was from Arizona. He went to Arizona State I think – the one in Tucson. My mother went to Cal [University of California, Berkeley].

Your major was political science?

Yes, political science and history were the two things that interested me at the time. I studied them; I wound up getting a major only in political science because surprisingly enough, the history department had a requirement that you take a course in medieval history, and another course in historical method. At age 20, I was uninterested in either one of those, so I said, Eh, it’s not worth it, so I didn’t take those two courses, I didn’t get a double major. Then when I retired from the State Department, I started writing history, and the first book was about medieval history. So I should have!

Tell me about your life at Stanford.

Well I didn’t join a fraternity, and I lived off campus for three years after freshman year. I guess I was kind of a loner. I hung around with my friends, and we played tennis, or just hung around. I was involved a little bit in student activities, but I can’t really remember which one of those were important, and which ones were just make-work. I had friends; we used to go out to Rosotti’s Alpine Inn in Portola Valley, which is still around. It’s on a road up to the hills. An outdoor beer garden. But not as frequented as it is now. My daughter lives in the area now. We go to Rosotti’s as kind of an occasion. It used to be, I don’t know, jerky sticks, beer, and pretzels, that was about all.

But, those were the kinds of things I did. I tried out for the track team. It was pretty obvious that high school skills weren’t good enough for really competitive college track, so I decided I was wasting time. I was in ROTC for a while, and they flushed me out [for] medical reasons, which I’m told by medical people now, was probably just the result of a bad test. I never thought about challenging it, which is interesting because if I had been an ROTC officer coming out of college, my career might have gone in a whole different direction. But it didn’t. I liked political science. I thought the teachers were mediocre. My faculty advisor was kind of out of date, I thought. So, put it this way, I never joined the alumni association. I didn’t feel strongly about it.

College was stressful. I was growing up. I was probably about a year, or at least a year younger than the other people in my class. I don’t know how that happened. I started school early – I can’t really remember. So I was socially and sexually probably pretty immature. Kids are uncertain at that age, about everything, and I was. I wasn’t very happy in college. I liked the school, I liked the learning, but socially I think I was kind of a misfit.

What was next after you graduated in 1957?

I guess I have to go back [to before graduation]. End of my junior year, I was going off on an exchange program – it was called the Experiment in International Living. We were going to Berlin for the summer. As kind of a trial run, I took the [Foreign Service Officer Test] entry exam in New York, on my way to get the ship to Europe. I had this summer in Europe, I actually stayed until Christmas time almost. Stanford is on a trimester system, so I could do that. While I was in Europe, I was told that I had passed the written test, and I was to come back and take the oral test. So I took the oral test before going back to Stanford. And somewhere during the oral test, they asked me, What would you do if we flunked you? And I said, Well, you know, I’ve got the Army – in those days everyone had to register for the draft, and you had to be ready for duty, or else have a better excuse. Since I didn’t have any good excuses at hand, I figured I might as well go ahead and do my military duty. So I said that. I said, I’d probably go into the Army, and volunteer and come back and sit for the exam again. At the end of the exam, they came to me and said, You know, we think you’re good material, but you’re just a kid, but we’ll take you, no questions asked, when you come out [of the Army]. So by the time I graduated, I already knew that was the promise I made to the State Department, so I went and signed up for the Army. You had to volunteer for a three-year commitment. Then you had to convince them that you were the right guy to go to the Army language school, which is what I wanted to do. I went to the language school and learned Russian. And that was what I did when I left college. I left college in June 1957, and by July or early August I was down at Fort Ord in California doing basic training. Then from there, went to the language school, then to duty elsewhere, and three years later I was out.

Was Russian difficult?

No, it was very fun. I really enjoyed learning Russian. They teach you for a year, and they teach you with specific military ideas in mind. You’re going to be either listening to the radio, or you’re going to be a prisoner interrogator or something like that. So you learn vocabulary that you don’t need normally, and you don’t learn a lot of vocabulary that you would need in normal life. So, my Russian wasn’t very useful to me. Basically not at all in the State Department.

Was working in the State Department the career you always wanted?

The State Department? [Yes.] It was a possibility. I had always thought of journalism, or something involved with living overseas or working overseas, or the State Department. My father after all – and most of the family friends who were journalists – were interested in foreign affairs. When my parents had friends over, they treated my sister and me kind of as adults, and we were invited to take part in the parties, and everybody was always talking politics. It just went the direction I was interested in anyway.

Do you think your parents expected that career for you?

I never felt forced into it. It was just the way I was raised. I guess we were always involved in politics, or international politics anyway. And the people who came through our house were always people who were in the same line of business, so it was natural to me to go that way.

How long did you work in the State Department?

When I came out of the Army it was July, and I think by September I was in the State Department. That was ’61, and I retired in ’96. That’s 35 years.

What were the career paths in the State Department when you entered?

In the State Department, you usually have an assignment. Your first tour, there’s training. Then your first assignment is usually some get-acquainted-with-how-an-embassy-works assignment. They put you in kind of an administrative position rather than a managerial position, because you’re managing local employees, but not managing yourself. Or a consular, you can do consular work as a junior officer. I did a year, or two years, in Washington I guess.

Then we went overseas, and in the last part of Washington and overseas, I was studying Arabic at that point. They needed junior officers to specialize in Arabic, and I thought my Russian wasn’t going to take me very far, so I better learn a language that they wanted. I mean I had French already, and a bit of Italian and things like that, but they didn’t need those. What they needed was the hard languages. So we went to Beirut, and I was a student. Then my first post I was administrative, or a junior member of the administrative section in the embassy. I did the personnel office. I did the security function. I did a couple other things, I can’t remember, but I was head of a section where I was the junior officer and a bunch of local employees who were actually doing the work. So it was experience in low-level management at the beginning. And then, my next appointment was in Cairo, and there I was doing economic work reporting on economic activities. So you get a little more responsible work each time, until you eventually go either into the administrative or consular work, where you become a reporting management officer, where you’re essentially reporting on what’s going on.

Which were your favorite assignments?

I had a lot of different ones. We loved Cairo because of the work and country, it’s a fascinating place. The easiest place we lived was probably Tunisia – that was years later. It’s like southern Italy. It’s a lovely country on the Mediterranean, with lots of Roman ruins and interesting scenery. I think the most challenging jobs were the ones in Washington, because you go back and forth between Washington and your posts overseas. Because they always involve many more layers of management issues, and responsibilities which are a little harder to penetrate than what you’re doing overseas, which is, generally speaking, representing the United States and reporting on the local activities, which is kind of fun. In that sense I still think of myself as a reporting officer. Somebody who goes out and finds things that we want to know, or don’t want to know. And report to Washington so they get an understanding of what’s going on in that country.

In the midst of all that, you married Olivia Collins and started a family?

Yes, our first child, Marian Elsa Brown [Sprague], was born in Beirut in ‘62 or ‘63. The second child – Louise Margaret Brown [Ingold] was born in England because the hospitals in Baghdad were not up to par. But she came to Baghdad at the age of one month or two months. Then the third child, Stewart Laurence Brown, was conceived in Cairo I guess, and born in Washington.

Tell me how you met your wife.

We actually met in 1958 when I was between the Army language school and Alaska, while I was still in the service. [Later in the conversation, Gordon Brown explained his military experience in Alaska where he was stationed at the end of the Aleutian Island chain monitoring Soviet missile tests. He said, “We listened to the police, air base, and other voice radio networks”]. Olivia was living in San Francisco, a guest of people whom we knew. She was from England, and so she didn’t know anybody. My mother knew her hostess, I guess. She was staying with friends of her family. And so they hooked us up a blind date, and it worked!

What was it like raising kids overseas?

Well in many ways it was easier, because it’s easier to get help. The difficulty was always finding the right stuff. I remember in Baghdad we tried for a while to keep chickens because there wasn’t a good supply of eggs, and milk was often canned milk and stuff like that. So getting supplies in some of the countries, getting good baby supplies was difficult. But you always had the help around. You didn’t have to worry about washing diapers because there was somebody to do it for $20 a week, or something like that.

How much time was overseas vs. the home country?

Well in the State Department, of course, you spend two thirds of your career overseas, and one third in the States. So between every second assignment or so, I worked at the [Washington, DC] State Department. My final overseas assignment was over in 1994, and I retired from the service in 1996. So our last move was 1994 – our last move from overseas.

Your kids were how old at that point?

By that point our kids were gone. When we went overseas in ’87 or something like that, to Tunisia, we didn’t have any children with us anymore. They were in college or out of college. They all went to college in the states. The two elder girls went to Duke, and the son went to George Mason.

What was life back in the U.S. like?

Well I was still with the State Department, and I spent my final two years with the State Department as an inspector of the embassies. That was the only time I ever got to use my Russian, because basically all the new republics, which used to be part of the Soviet Union, had been independent for maybe two or three years by then. They were due for an inspection. They were start-up embassies run by people who probably didn’t know much about what they were doing, and they needed somebody to come out and tell them how to manage their business a little bit better. Nobody in the inspection corps wanted to do it. I joined the inspection corps right when this came about. So in the end, I wound up going to all the republics that had broken off from the Soviet Union — the ‘Stan’ countries in south Asia, all the Caucasus, Moldova, which is back in the news, and so on. Leading a team of inspectors, which was great for me because I got to use my Russian and see the country, or at least the outskirts of the country, if you will. At least the semi-independent republics. I learned a lot. One of the things I learned was that I was damn glad I had kept my Russian skills up because these are miserable places to live, some of them. Really awful. During the Cold War, we [in the United States] were scared of the Russians militarily, and their science was so terrific, we built them up to sort of be this super power. But really, I spent a lot of time in Russia too, as well as the republics, and the public facilities outside of Moscow. The public facilities, schools, hospitals, I don’t know what else, were out of the 1930s. I mean it was a pretty backward country.

What did that experience lead to?

Well I inspected those embassies in my last two years in the State Department. Then I traveled some more because one thing I wanted to do was keep a connection with those countries. An organization called “The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe,” the OSCE, has a program where they send inspectors out to the elections in these countries, trying to encourage the countries to remain democratic. So I signed up for a lot of election observation missions for the next five or eight years I guess, after I retired. That wasn’t a full-time job. I’d do one a year or so, but it still kept me connected through that kind of travel.

We did a lot of [personal] travel after I retired too. We had bought [our] house on 32nd Place in Chevy Chase DC in 1964. That was after our first post overseas. We came back from Baghdad where they had what they call a hardship allowance. If you’re living in a country where you wonder about the quality when you can’t get eggs, they pay you a little bit more. So we had some money in the bank, and we came back to Washington. And since I had grown up in Washington, I remembered that my parents had always said, you know, this is a great town to own a house in. Because there’s always a demand, there are always new people coming to town, and there’s never enough supply. So we started looking for a house. We had returned from Baghdad, we had a little money in the bank. We wanted to live downtown but by that time Georgetown was too pricey. This was ‘65 and it was already getting pricey in Georgetown. We looked in various places, let’s say, North Capitol and whatnot. But we came out to Chevy Chase, and I didn’t know where Chevy Chase was, really. I thought it was somewhere just south of Baltimore, or something like that. We liked the house though. We were told the school was good. At that point we didn’t really have children in the school, so we didn’t really care about that. We thought the house was right, so we bought the house. When we came back from post, we always managed to time it so someone was [moving out of] the house.

You rented it out while you were away?

Yes, we just lived there while we were in Washington. We rented it out while we were overseas. So we had this very nice house to come back to each time. It worked out well, and we could travel from there with ease. We almost paid off the mortgage. Oh we did pay off the mortgage. We paid off the mortgage twice actually. When we refinanced it I supposed, then when we sold it again. So anyway, the house was kind of our little bank account, if you will, in Chevy Chase. It allowed us to come and go frequently. After I retired, for a while I was the new executive director of a new business council called US Qatar Business Council. I don’t think they ever really knew what they wanted to do with the business council. They had kind of been convinced by the Qataris that they [American companies that founded the council] put up the money for it as sort of a good will idea with the Qatari Embassy here. I was their executive director – the first one – and we spent three years kind of spinning their wheels, and I eventually left. They were just about ready to ask me to leave, so it worked out fine. The place is still operating and it still doesn’t really have so much to do, as I can see. It’s one of those typical Washington things. But what I really did when I retired was I decided I was going to write some books. So I spent 20 years writing books.

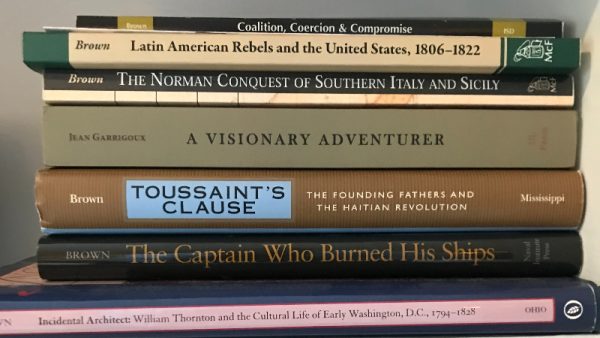

What did you write about?

Almost all of them history. The first one was really about the eastern Mediterranean. About the connection between the East and the West. A bunch of young, I don’t know, “freebooters” I guess you could call them. From Normandy, they came down to southern Italy in the 11th Century and eventually built a kingdom for themselves. They fought both the local people and the Byzantine Empire, or the Roman Empire in Constantinople. And the Arabs in Sicily. So it was kind of an East meets West in the Middle East discussion. It was kind of an interesting book, because it hasn’t been written up well in the United States. I enjoyed writing that, but I had a hard time selling it to a publisher. But I enjoyed writing it, so I thought, this is what I want to do.

So I thought, okay, I’ll concentrate on early U.S. History, not American history. So I concentrated on the area between our Constitution and the Jacksonian Revolution sort of, in the 1830s. Sort of a 30-year period where we were really just getting set up as a country and learning how to deal with the big powers. Learning how to screw the Indians, and establish ourselves as a future continental country. So it was a really interesting period, and I wrote a number of books about it. Both about Washington and our foreign figures at that point.

Were you using prior knowledge about history, or did you research?

I had always been interested in history. Almost nothing I had done in work really applied to this. So I had to do it all from scratch. And I won’t say that there were – what should I say? I didn’t plow any new ground, and the academic reviews were mixed about the books, so I wasn’t really adding much to world history. I was adding a lot to my own sense of enjoyment. I really enjoyed that.

You became a real Washingtonian. Was that always your plan?

I had not thought of myself that way when I was younger. When I would return here from overseas assignments, I hadn’t thought of it in those terms, as a home. I still thought of myself as a Californian. I still in a way think of myself as a Californian. But when I go out there to visit our daughter, I realize I’m not anymore.

In addition to writing books, you got involved in other projects. Did politics interest you?

No, not politics. Somewhere along the line I had come to the conclusion that what Washington really needed was a solid lower-middle class. A home-owning middle class. And [I realized] that home ownership was the way to get that. So, I was looking for housing groups and I worked for a while with housing charities, and I thought that wasn’t the way. We were keeping families in homes which were substandard, and basically we were just keeping them in places that we shouldn’t really have been renting. Fire and sanitation problems. We were keeping the families together, that was one thing. But really, we were giving them shit to live in. So I decided that home ownership was really the answer, and that fits the pattern of the organization Habitat for Humanity. So I worked with Habitat for Humanity for 10 or 15 years. I was chairman for three, I think, and I liked that. That was worthwhile work. I left there in 2016 or 2017.

Wasn’t President Jimmy Carter involved in that?

He was involved with it ever since he left the government as far as I know. It was started by a guy down in Georgia, which is how Carter got involved with it. Carter became their biggest public relations kind of asset because he came to one of our builds when I was chairman. You know, it brings the press, it brings the people who are interested in seeing what you’re doing, and all that stuff leads to donations, which is nice. Because if you’re a charity, or public relations outlet like that, you need support. You don’t do it on your own money, you do it on other peoples’ money.

Did you have any direct interactions with President Carter?

I shook his hand when he was here, but that’s about it. Actually, at one point or another, I would have had a lot more connection with him. While we were in our last post, out in Western Africa, I knew I wasn’t going to get another embassy [assignment], so at that point I asked myself, I’m probably going to have to retire in the next few years, so what am I going to do? And I got a phone call from one of my ex-colleagues in the State Department. He worked with the Carter Center, saying, Gordon, we want you to come. We’ve got a project for you, and you’ll be the director of x, y, z or something like that. I thought about it for a while, and I thought, Well, it would mean moving from Washington to Atlanta, and I’m not a southerner by nature. And to be perfectly honest, I wasn’t entirely convinced that I liked the Carter Center’s kind of ‘holier than thou’ way of doing business. I’m a little more cynical. So I said no. I was tempted though, because the work sounded interesting. The salary was good. And I’m sure that living in Atlanta is probably pretty comfortable, but I just didn’t want to do it.

I didn’t ask about what your wife was doing during your postings.

For the first couple postings, she was raising children. We came back to Washington and the kids by that time were all in school, so she didn’t have that much to tie her down anymore. I shouldn’t say that, because god knows a housewife has to do the cleaning, the plumbing, the washing, the shopping, and all those other things. She got a job with a real estate company, and she was their office director. She sort of ran the office for a company that is no longer in existence. That would have been in the ‘80s, when we were here for almost eight years. Then overseas, at one point when we were in Saudi Arabia, she worked for an American contractor, which had an office in Jeddah where we were living. But their headquarters were in another city, so she was there since the airplanes all came to Jeddah. But people came there first, and a lot of the government offices were in Jeddah. So she sort of ran an office for these people who were coming and going for the contracts that they had. She did essentially administrative stuff for them. But it was good for them, since in Saudi Arabia, if you’re a woman you can’t drive. Or you couldn’t in those days. And this got her a chance and gave her a financial reason to pay for transportation to go out everyday. She’d go out for four hours, and she had a driver, who would take her to the shops on the way home, and so on. So she got out, she liked that. When we were in Tunisia, she took a job at the embassy, being kind of the morale officer in the personnel department. She had some jobs overseas, but most of the time she was raising our children.

How did it work for the kids, switching up schools?

When we were here in Washington, obviously they went to Lafayette, Deal, etc. The two girls went through the whole thing. The son, who was five years younger than the second girl, went to Lafayette. He went to Deal for a year. He’s – should I say – the least aggressive of our children in terms of wanting to advance himself. He was happy with having Cs, and we tried to convince him that having Cs at Deal wasn’t good enough. He was hard to convince, so we put him into private school. First, St. Andrew’s School, then up in Mercersburg, just across the line in Pennsylvania. A small, private academy. He went there and we went overseas again, and he was there on his own. He said it was a prison, but I still note that most of his friends are still from that school, so he had a good time. I think he went over the wall more than he should have.

Eight years ago you stopped working for Habitat for Humanity?

Yeah, I had been chairman of the board for three years. The management was changing, the whole system had changed. I think the financial – you’re probably not aware of this, but the financial collapse in 2008 was all based on the fact that the real estate market was all wrong. The financing was all wrong. And everybody came out of that collapse of the financial world – it took four or five years to get out of it really. The lesson everyone learned was that the financial models that everyone had been following weren’t any good anymore.

Habitat had been raising its money through private donations, and support from institutions – how should I say – larger charitables. We raised about 30 to 40 percent of our money through larger donations. It just dried up completely. We couldn’t raise money anymore, and the Habitat guidance, which had always been, Habitat runs its own banks, Habitat sells the houses, manages the mortgages. Habitat wants to know its customers. So it wants to be the financier for these people because you’re selling them a lifetime house. And we did a lot of looking over their shoulders, you know, trying to keep them out of the hands of people who offer them a $50,000 advance if you just sign a second mortgage kind of thing.

But the whole model changed and Habitat headquarters said okay, we’re going to have to use more commercial finance. Basically now, Habitat here in Washington is simply a contractor for the government. The government offers us land, gives us the possibility of building houses – when I say ‘us’ I mean Habitat. You can build houses on land offered to you by the government, and they have a lot of programs for financing and building the houses. And you’re just contracting the government basically, for low-income housing. It’s not as charitable, it’s almost all bureaucratic at this point. That was changing as I was about to finish my chairmanship, and I decided I really didn’t understand the new world of finance, and I wasn’t set up for it, so I left. I hung around on the board for a couple of years, but I didn’t have a serious management job anymore. I think sometime before the [COVID-19] pandemic I had already stopped even contributing. I just sort of felt they weren’t doing what I thought they were doing anymore. The end is still the same. The end is still to provide their own housing to lower income families, so they can raise their families in a way they couldn’t when they were renting. But the way of doing it is so different now. I just didn’t want to be a part of it anymore.

What have you spent your time doing instead?

Well, writing those books took a lot of time for a while, and I’ve written my last book, I guess. When I ran out of book projects, I translated a book from French. Then I spent a year or so asking, What am I going to do next, and trying different things. I went up to New York once I remember, and spent a day in the New York Public Library looking at the records of a guy who I thought was a fascinating guy who might be a good subject for a biography. I discovered his handwriting was so impossible to read, and I thought, I’m gonna spend thousands of dollars in this library trying to translate 200 letters, you know, because of what hotels in New York cost and so on. I decided it’s financially not worth it. To write a book about a second- or third-echelon guy back in the early 19th century. I’d be lucky if I got a publisher, and I certainly can’t spend $10,000 to $13,000 to do the research. So I ran out of subjects to write up really.

How long have you lived at Ingleside?

Since the pandemic, yeah I’ve been here. Pretty much my outside life is now in low gear, put it that way. I had been volunteering at the Smithsonian and doing other things, but that all petered out I guess.

You teach at the OLLI [Osher Lifelong Learning Institute] program at American University, correct?

Yes. It’s basically old farts talking to other old farts, but we all have fun doing it because those of us who have something we enjoy talking about can go do it, and some people can come and actually learn something from us. I think it’s delightful that anybody past 80 wants to learn.

What have you taught there?

Basically I’m doing the easy thing – I’m taking my old books and turning them into courses. I’m doing it one more year I think. I’ve taught the same course for two years; I think three years is probably the maximum I can teach it. The first time I had 25 students. Last time I had only 15. I’ll have only five next year, so I’ve run my course.

You mentioned you travel to California – to visit your children, grandchildren?

The grandkid is actually here. That’s our first daughter who’s out in California. The grandkid is actually here in Washington. She’s a lawyer living in town now, on 16th Street, getting a good salary with a New York law firm. So, she’s here, but we don’t see her. She’s got her own life, she’s busy. Her mother comes to town periodically, she’ll be here, maybe next week [but] she’s not here to visit us, she’s here to visit her daughter.

We went to Richmond to visit our other daughter for Thanksgiving and New Year’s this year. We were in California in the fall. We went back to Yosemite. We probably take a trip to California once a year. We see the Richmond family. Our son, who’s the youngest, just lives across Western Avenue from here, so he’s pretty close. He’s divorced, and his two kids are in college so he doesn’t see much of them.

What else keeps you busy?

When I’m here, I’ll tell you what I do. I’m editor of the newsletter for this organization here [at Ingleside], which is kind of fun since I still like being a journalist in a way. There are always these committees, which I told you about. So I’m on a committee or two, which spends a lot of time spinning its wheels, but sometimes gives good advice to management, which the management sometimes pays attention to. I still like reading things. I build a model ship every couple of years – I’m not artistic so I create things that I can build.

How do you do that?

I’ll show you my little workshop when we leave here. When I was a kid, I built model ships that size [pointing to a model in his sitting room]. In a scale of 1:300, which is really small.That is a famous historic ship – the [HMS] Victory – the one that (Lord) Nelson won the Battle of Trafalgar in 1814. Now I can’t see and I can’t control the shaking of my hands well enough. I’m building it 1:60, where one inch becomes 60 inches. But that [one] was one inch and becomes 300 inches, which is a lot more. It’s fun just to do something like that. It gives you something to think about in addition to other things you have to think about – put it that way.

This is a sociable place. This retirement home is full of a lot of people, almost all professional people. We have doctors, we have politicians, we have artists, we have a lot of writers, people who have written professionally, we have medical people. So there are lectures and talks, and community activities. And we go down to the dining room and dine with different people each week. So it’s a pretty interesting place just to live in. You know, the activities are limited to what old folks do.

Do you spend much time out in the community?

Not that much. Most of our cohort on 32nd Place are gone. They’ve all moved out too. All the people we played tennis with for years, and played golf with and so on, have either moved out or died. So your social life sort of changes. We see some of them occasionally, but it’s gotten down to, you have to call them and ask if they can go out to dinner since we can’t invite them to the house. Most of them are out of their houses too. Or we go to the theater with old friends. Over the four years we’ve been here, we’ve noticed that we’ve kind of lost our connection with the community.

How has Georgetown changed since you grew up there?

By the ’50s, by the time Kennedy lived there, it became the fashionable place to live. I was once invited into our old house. I happened to be in the area so I drove by N Street and I noticed they were doing work on the house. This was maybe 15 years ago. I walked up to the house, and a little girl came out, maybe 12 years old or something like that. I said, Do you live here? She said she did, so we started talking. She invited me in, and I looked around and you know the house, the body of the house is a marvelous place. Big, tall ceilings. Tall windows. Architecturally not unusual, but just good. When we lived there it was kind of not well maintained. Still as bad as 1860 or 1840 character pretty much. But it had been all gussied up. The basement, which used to be a place for the furnace and the work room downstairs, is now all fixed up like a den, and stuff like that.

So you know, how did I get on this? It’s a totally different world, anyways. I don’t really feel nostalgic about it, but I do know that I’ve cut off connection. I was volunteering downtown to teach English to foreigners up until the year before last. I gave up. The buses weren’t regular enough to really count on. It took me an hour to get down there every morning, an hour to get back. I was wasting more time on public transport than I was teaching. So I let that spin by. The pandemic ruined my job at the Smithsonian because my boss moved on. They closed that branch, and I had nobody to recommend me. So I couldn’t volunteer at the Smithsonian anymore. One thing after another, it just cut off connection. And I’m getting old now, so it isn’t much fun anyway to spend a five or seven hour day. I was working, let’s say, five hours a day as a volunteer at the Smithsonian. Transit added an hour each day. When you’re older, you get tired faster. If you don’t have interesting work, it isn’t worth it. The Smithsonian would be a great place to work if they just had a better way of, what should I say, recruiting and incentivizing volunteers.

At which museum did you work?

The American History Museum. When I tried to go back, I was hoping that I had some contacts in the archeology department, in the natural history department. That didn’t work out. I chased that for years. The first year we were here, I chased that as hard as I could. Their staffing dropped after the pandemic. They weren’t taking any volunteers since they were still worried about the health conditions. I was trying to row upstream, it just wasn’t pulling it.

You mentioned theater.

We still have a subscription at Arena Stage, downtown. But even that’s getting to be a pain in the ass. Ever since they built the Wharf project downtown, and The Anthem is there. The traffic jams down there! You used to be able to go down there in a half an hour. Now it takes 45 minutes to get there, and so on. Another organization. You know, things change. While I was writing these history books, I was pretty active inside the Association of Oldest Inhabitants of DC. It doesn’t mean old in terms of age. They were put together after the Civil War for some other reason when they were trying to prove that the government had a strong support in the community, because there was still talk of moving the capital to Kansas City or something like that. Anyway, this organization used to have monthly lunches downtown in one of the hotels down at the Wharf. Well those hotels have been demolished. You could park at the hotel, it was a country hotel where there were parking lots. Now there are 8-story buildings. It’s $8 for parking, and $50 for lunch. It takes you four hours to have a two-hour lunch with people we don’t know anymore anyway. So you drop out of things. When you’re older than 70, you begin making calculations as to whether it’s worth the trouble.

Since you grew up her, are you a Commanders [formerly Redskins] fan?

They’re kind of boring in a way. Put it this way — I’m more of a fan when they’re winning. This year’s great. It’s fun to see them winning again. Yeah, everybody remembers the years when you had winners. I was watching the Steelers game last night against the Baltimore team. The Steelers are the kind of team the Redskins used to be. A lot of really hard running football, they go in the dirt and stuff. Football’s gotten a lot flashier. All the trick plays they have where you can’t even follow what the guards are doing now. The guards aren’t just sitting there and blocking. They’re running downfield and so on. Blocking 10 yards away from the line of scrimmage. It’s a way more complicated game. Now I don’t really understand it that well anymore. I’m not that big a fan, but it’s still fun to watch. To be perfectly honest, if you can find a way to eliminate the timeouts, they’re endless. It takes three hours to watch an hour and a half of football.

To be perfectly honest, my wife thinks I’m crazy , but I follow English football [soccer]. I follow the English teams, and the French teams, and the Spanish teams. I like soccer because it’s continuous action. And a lot of TV channels, well they have a variety of channels too. You can find a lot more European football on TV than you were able to 10 years ago. So I watch that very regularly, as a matter of fact I’m taping something right now. Right now Madrid is playing Barcelona this afternoon for the championship of Spain.

Who are you rooting for?

I don’t really care. They’re good players, I just like to watch them play.

Before we wrap up, is there anything else you would like to talk about?

Well I’m surprised you haven’t asked more about Chevy Chase [DC]. Chevy Chase was a really good neighborhood. What we enjoyed about it – well for one thing, it was really convenient for me. There were always State Department people living in our part of Chevy Chase. So all those years I worked in the State Department, I was able to carpool. They gave you a parking place in the building if you had a carpool. So we were able to carpool down to the State Department, down to Foggy Bottom. The carpools were some of my best memories of working in the State Department because the State Department is like any large organization, divided up into little fiefdoms, where you work for the Latin American division, or on the Middle East division, or on the Asian division. Somehow or another we always managed to get a carpool that had representation from all the divisions. So you got most of your office gossip about what was really going on in the other divisions during your carpool rides. So that was one of the advantages of living here, and it’s a nice commute down to Georgetown, or to Foggy Bottom, from here.

So I think we were very lucky that we bought a house in Chevy Chase. We had one of those old – I guess you’d call it Edwardian – front-porch houses. Big front porch. 1908, 1904, 1908. I think it was actually the sales model for – what’s the name of the stream that runs from Western Avenue? Pinehurst, Yeah. Pinehurst. The Pinehurst Development Company developed those streets down there, and I think our house was their show house, because it was the first one there. It was two houses up from Tennyson [Street] on 32nd Place. It was a good old solid house. Built with timbers you couldn’t saw through with water. It was oak timbers. It was really amazing and well built. Because any time we did a renovation there, you would get inside the walls and the people would say, oh my god. The lumber was so much different. But anyway, we enjoyed living there, and I’m a fix-it guy, so it was all fine for a while. Once you get past 75, you’re a little tired of being Mr. Fix-It, so it wasn’t so much fun later. But you know, we enjoyed it. The schools were good, our neighbors were good. We live here on the 5th floor with two of our neighbors from 32nd and Tennyson. They happened to move at the same time we did, to the same floor of the same building, which is kind of amazing.

How has Chevy Chase changed in your time?

There’s a lot of pressure on Connecticut Avenue. We all know that fight about what happens to the library and community center there. Yeah, I mean Chevy Chase has changed. The development of Friendship Heights has changed a lot. I mean it’s brought some nice stores here, but it eventually pushes back the neighborhood. It pushes back. But that’s okay, it’s alright, it’s inevitable. The urban planner in me, which isn’t a very large part of me, says, yeah it makes sense to have denser housing communities in town rather than going out to far-off Loudoun County to build a community, a city. But I know it’s painful to each neighborhood that gets changed. I’m not sure if it’s the beginning of the end for the neighborhood, in a way. I can see if maybe 20 years from now, all the way up to Nevada Avenue will be more apartments buildings and so on. And eventually from Nevada to Utah, who knows. I’m glad that we’re not part of the change anymore because it’s a little traumatic to see change happen in your neighborhood. I can see that it’s going to happen – it’s just inevitable. Every time you turn around, some house has gone down and a bigger one has gone in its place. But what I suspect will happen is some of those people who build the bigger houses will, 20 years from now, sell a piece of land to a four-story apartment building. Rezoning, I suspect, is going to happen.

What advice would you give to the generations to come? You’ve lived a very full life with plenty of experiences.

Well, yes. I can look at my own extended family and see how a narrow world vision impacts people. For instance, I have two relatives about the same age. One is purely professional. Focuses on his profession and his politics. The other one is much more interested in a broad field of things. He loves to travel, loves sports, is open to all kinds of cuisine and so on. One of them is happy and the other one isn’t. I’ve seen a lesson there about being open to a lot more in life. Which I think is strong.

And among the younger generation, I have watched one person grow up who is the least interesting [of that generation] and the least happy too. He doesn’t have the imagination that the others have, and he’s a “Joe six pack.” Is that a term you understand? It was a term from about 15-20 years ago. “Joe six pack” is a factory worker who goes home, opens a six pack, drinks beer, then goes to bed, etc. Has no life outside of watching football and talking to his wife and children, and his work. I find his life is just not very rich, and I don’t think he’s very happy either.

If I have any lessons it’s to keep your eyes and ears open to anything new. The richer life is the more fun life. You may not be a scientist, but there are some scientists who are totally focused on what they’re doing. Actually we have a couple of those in my cousins and so on, so I’m thinking what they do. I don’t think they’re very happy. They really like their work, but they don’t have any peripheral vision. It’s kind of a limited life in my opinion.

Living overseas makes you understand the way other people work. Being in the Army makes you understand other people’s reality. I mean, this building is full of professional people. They don’t understand why [other people] vote for [President Donald] Trump. Being in the Army made me understand the vote for Trump in a much different way. I understand the problems that lower-middle class people have. About just eking out a living, and you know, raising their kids in an easy way, and so on. They’re much more susceptible to agitation when things are going bad. I think that comes from a lack of imagination. It comes at all levels and classes in society. The idea is to keep your ears open not just socially, but intellectually about the world. I think I’m happier for that. It doesn’t make me a better person in any way, but I enjoy life more.

END

© Copyright Historic Chevy Chase DC

Oral history interviews may be copied for personal, research and/or educational purposes only under the fair use provisions of US Copyright Law. Oral histories accessed through this web site are the property of Historic Chevy Chase DC. the copyright owner.

Use of these interviews is subject to the following terms and conditions:

- Material may not be used for commercial purposes. Short quotes and references are permitted for instructional and publication purposes.

- Users must provide complete citation referencing the speaker, the interviewer, the date and website with URL address.

- Users may not re-post or link the oral history site or any parts of it to another program or listing without permission.

Questions about the use of these oral history materials and requests for permission should be directed to hccdc@comcast.net or HCCDC, PO Box 6292, Washington, D.C. 20015-0292.