Narrator: Elizabeth Jane Pratt MacLeish, age 84

Date of interview: Jan. 25, 2025

Location: MacLeish’s apartment at Knollwood in Washington, DC

Interviewers: Caroline Reilly, age 17, with Tim Hannapel

Transcribed from audio recording by: Caroline Reilly

Abstract

Born in England in 1940, Jane MacLeish grew up in wartime London, the daughter of a surgeon and a nurse. She remembers the air raid shelters, the blacked-out windows, and the sugar her “naughty” mother snagged on the black market. Despite the war, childhood was an adventure—digging traps for imagined German invaders and relishing the candy sent by Canadian hospitals.

MacLeish’s education was anything but traditional. Resistant to the rigidity of school, she was instead taught by her father—a Renaissance man who painted, sewed, made fabric, and built furniture, weaving life lessons into everyday skills. By age 21, restless and seeking adventure, she left England for America, sailing across the Atlantic as the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded around her. Her first impression of the U.S. came with culture shock—barbed wire in Florida following the Cuban Missile Crisis, segregated bus seating, and a secretarial job that felt stifling.

Opportunity, however, had a way of finding MacLeish. A chance call from a friend led her to board a Greyhound bus bound for Canada, only to be denied entry at the border. She pivoted again, this time to New York City, where she found work at St. George’s Church. There, amidst the vibrant energy of young professionals, she discovered the power of community and a city full of possibilities.

One of her most defining adventures fell into her lap and she was bold enough to grab it. A Columbia law student researching poverty in Appalachia needed a photographer. MacLeish volunteered to join him, eager to see the country beyond the city. The trip was eye-opening – coal towns abandoned, families surviving without heat or plumbing. The experience was transformative in many ways: She and the law student, George, fell in love and later married, bringing her to Washington, DC, where she raised two children and reinvented herself as a garden designer.

Washington became the backdrop for the next chapter of her story. When her marriage ended, she sought a new purpose. “Notice what you do, not what you think you should do,” someone advised her. She realized she was happiest in the garden. Without formal training, she immersed herself in landscape design, building on talent that could trump credentials. Over the years, she worked with some of the most prominent families and institutions in the country, shaping landscapes for the Rockefellers, Dumbarton Gardens, vice presidents, and even the White House.

MacLeigh’s life has been one of risk-taking, resilience, and regeneration. Now in her 80s and a resident of Knollwood Life Plan Community, she remains deeply engaged in conservation efforts, leading projects to restore historic landscapes and protect urban green spaces. Reflecting on her journey, she offers simple yet profound advice to younger generations: “Be brave. Keep learning. Love yourself. Trust yourself.”

Caroline Reilly:

We’re here to interview Jane MacLeish, who spent her career designing beautiful gardens in homes and parks all over the country, including at the Washington, DC, Observatory, the home of U.S. vice presidents. Somehow she did it without a shred of a formal education, so we are eager to hear how. I also know that you lived through the Blitz in London, and got an ocean-front view, sort of, to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Plus, you’ve taken a Greyhound bus across the entire United States – twice! – something most Americans can’t say they’ve done. We’ll dive right in. Why don’t you tell us where and when you were born.

Jane MacLeish:

Ok, well I was born in England on November fourth – November fifth is a very big day in England – it’s called Guy Fawkes Day.

The year was 1940?

Yes, 1940. I don’t remember it [laughs].

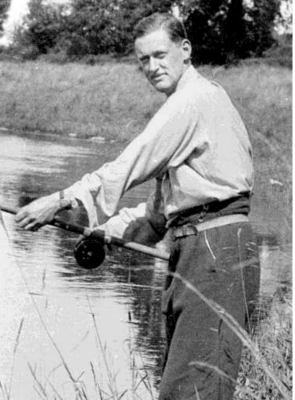

My father, Frederick William Markham Pratt [1898-1965], was a surgeon in London and my mother, Katharine Elizabeth Whistler “Betty” Pratt [1907-2001], had been a nurse. And we lived in Willesden NW2 in London in a sort of Victorian house. And it was the beginning of World War II. And, I always remember, we had long black curtains that came down to the ground because you had to do blackout. And my mother put colored ribbons horizontally at the bottom of the black. Red, orange, yellow, just to give it a piquant. Read PDF biography of Frederick William Markham “Bill” Pratt »

And I remember the air raids. We had an air raid shelter in the garden. So that was a very square concrete building, half underground. And it had shelves inside, wooden shelves, so you could go and lie in it, you know. And we’d be woken up in the middle of the night with the air raid sirens, so we’d be wrapped in a blanket and taken down and we’d lie on these things and wait for the bombs to stop. And we thought it was great, you know, real fun. And we would dig holes for the Germans to catch them and put twigs over the top, you know. But I remember that vividly.

And we had a cook from Hungary. And her husband was in a prison camp. He was allowed boxes of food every now and then. And I remember putting the boxes of food together to send to Hungary to him. And you know, Hungarians like paprika – I remember the red pepper and the things we put in the boxes – and sweets.

And we were also very spoiled as kids because the Canadians were very generous to the hospitals and sent wonderful tins of sweets, candy for the kids, and they couldn’t use it all, so we got it. And we were allowed one candy at each mealtime. A big, big treat for us – myself and my older sister and younger brother. There was no sense of fear. We were not scared. I do remember looking up at the sky and seeing lights. Those must have been bombs, or balloons? But I don’t remember terror. We thought it was hilarious and we were out to catch the Germans and make holes to boobytrap them.

How old were you at this point?

About 5 – 4 or 5. Then my mother took us – we had a house in the north of England in the Lakes District – she took us there and my father stayed in London. One of the things the Brits did was take all the road signs down so if the German paratroopers landed they wouldn’t know where they were. And, we were out in the wild and we would sleep under the dining room table and we each had a shotgun [laughs] … to get the Germans. So that’s what I remember of the war. But the worst thing was the cold, like no heat in the house. Damp. Cold, cold, cold. And my hands and feet would blister with it. I remember that, just things called chilblains. Have you ever heard that word? It’s when your skin dries out and you get these sores.

My mother was very naughty and bought what’s called black market sugar in the Lake District, which means it’s under the table. She was born naughty. And my father, because he was a doctor, had what we call “petrol coupons.” Most people couldn’t buy petrol – or gas – for the cars, so he could come up and get us to take us back to London. And we three kids were in the back of the car terrified in case there’d be a car crash and there’d be sugar all over the road. And we’d be picked up. I mean, I remember that vividly. The other thing I’ll tell you is very strange. But the house we had was Victorian. And that meant there was a lot of sort of colored stone and brick on the floors and tile, and I loved to scrub it and keep it clean.

That’s not strange to me. My grandma used to have me wash the windows or clean the silverware, and I loved it. I would get a broom or a mop and clean the floors. And my parents’ friends would come over and be like, is she okay? Is she being punished?

Well, we’re kin. Yeah. I don’t know why. I just loved it. So, people would come, there’d be this little four-year-old scrubbing the floor. Yes, that’s really what I remember.

Tell us about your siblings.

I had an older sister who is not with us anymore. She was two years older than me. She was adopted. My father was a senior surgeon in a major London hospital, my mother was a nurse, and they had a baby. And as everyone stood round he [the baby] strangled on the cord and died. And then my mother was told she couldn’t have any more children so they decided to adopt my sister. [Anna Catherine Pratt Pitt], 1938-???? had the same birthday as my mother. She was wonderful; everybody loved her. She died suddenly [from cancer], about five years ago. It’s a great loss.

How did you and your younger brother come into the family?

My mother [ended up getting pregant] and I was delivered by cesearean. So was my brother, James Edward Pratt, whom I adore. He was born two years after me. He’s a tree pathologist in West Linton in Scotland, and he’s a sort of Renaissance man like our father.

What was your childhood like after the war?

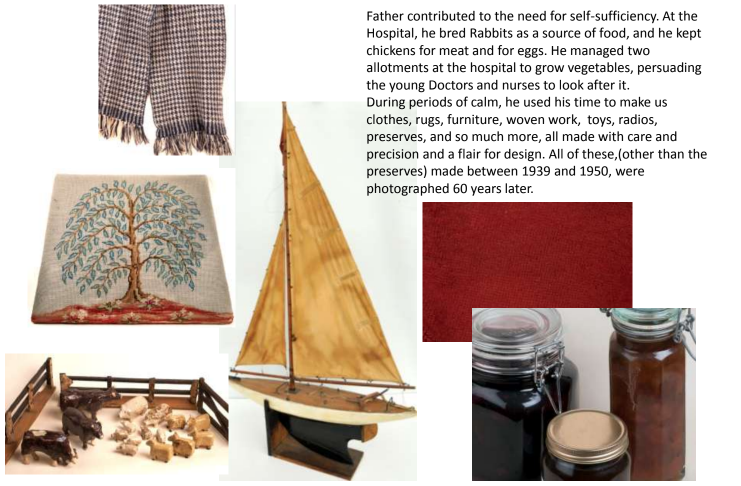

Well, I didn’t like school, so I wouldn’t go to school. And so my parents really had trouble with me about that. I would hide all day and not go to school. And finally my mother gave up and took me away from school. And she said, “You can help me run the house.” So I did that – not very well. And then my father, who was a Renaissance man… he was extraordinary. He taught us to paint. He made our clothes. He made the fabrics, he wove the fabrics. He made all our furniture, our school desks. He taught us. There was a polio outbreak in the hospitals in England and he was a surgeon, a children’s surgeon. He didn’t want us to go to school. So, he would teach us. And the local education officer came around and said, You know, Mr. Pratt, we’ll put you in jail! And he answered in ancient Greek that he could well teach his children. So he taught us to paint, taught us to shoot, he taught us to skin the animals, he taught us to make leather. He taught us to sew, he taught us all this. So that was the kind of education I got. It wasn’t academic.

But it’s amazing.

Yes, amazing. It was amazing. And the older I get the more amazing it is. And so, everyday school – sitting in a row in our uniforms – didn’t quite do it for me. And so there was this sense of me being radical and not fitting in. And so my father gave up – I think he was exhausted by the war – and he said, Well, you know — and this is what they said in those days – Just get a secretarial course because you’ll get married, but if it goes wrong, you can be a secretary. This is how they looked at it.

I remember when I was young I was always worried about my father. We had pea-soup fogs and he had asthma and it was aggravated by burning coal and peat and that’s horrible, you know. He would have to go out at night and you could almost not see your headlights, and as a child I was terrified he would die. And every morning I would go to his bedroom door and listen to see if he was alive.

My brother James has compiled a family history about my father. I’ll send it to you. [Read James Pratt’s family history here]

I was really scared of my mother. She was too strong. And that’s why I ran away [to America]. She was just too strong and it’s hard to be strong. I’m strong but luckily my daughter is not scared of me. I’m more scared of her [laughs].

What was it that scared you about your mother?

My mother was very bitter. She came from a distinguished family. Her sisters were part of the Bloomsbury set, very artistic. She was the oldest. Her father drank. She would run away. They put her in school, and she ran away from school. She decided to be a nurse and that’s how she met my father. But when he asked her to marry him she thought he was joking and slapped him and didn’t see him for, like, five years. [But eventually] they met again. She adored him, he adored her.

I think had my mother been able to have [modern medical] therapy, she would have been a more [balanced] person. She was very strong and very, very weak. In many ways, I’m very much like her – very strong. But I’m not bitter. I just didn’t want her to know me. It’s really, really sad. So I hid myself and I was never able [to open up to her before she died]. It’s so tragic.

So anyway, I did the secretarial course. I don’t remember what work I did in London, but I thought, To hell with this, I’m leaving. I was about 20 or 21. I had a godmother who lived in Fort Lauderdale and she said, Well, I’ll get you a green card and come. My parents were very decent about it. It must have killed them, you know? They drove me to Southampton and put me on the ship. And off I went. Tumdy tum tum tum. We were in the middle of the Atlantic when Cuba [the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962] happened.

So they stopped all the ships. Every ship in the Atlantic stopped. And we sat and waited to see if the Russians would turn back, which they did. But it was a pivotal time. The world was on edge. What would happen? Would the atomic bomb be used?

And then the Russians retreated and so I came into Fort Lauderdale. And that was just—it was barbed wire everywhere and security and all our cameras were taken.

That’s terrifying. Did you understand the gravity of it in the moment, or was it just like, distant?

I’d say it was a mixture, sort of amused concern. Does that make sense?

I equate the amused concern to what I felt during the Covid-19 pandemic. I was a kid, like 11, and every day some new bad news would come in, but we were all isolated, so it didn’t feel close. It felt very far away.

I think that could be a way of protecting oneself, you know, not to absorb it. Or just to be, I think, sort of innocent. I didn’t know anything about the world. I didn’t know much. What I wanted to do was party, you know? So, I don’t know. Yeah, I think I wasn’t afraid. Just … sort of curious. We were having so much fun on the ship – you know, one bonded with other people – and it was all sort of jolly.

How long were you on the boat?

Probably about six days. And then we came into Fort Lauderdale and that was really (shocking.) And the worst thing though, was my godmother’s husband met me and he said, Now, I’m gonna give you one piece of advice. Never go to the back of the bus.” And I thought, oh, God, you know? For a free spirit, being told (that back seats were for Black people, and the whites sat up front) the minute I got on land in Florida I was hit by it.

Welcome to Jim Crow. We’re discussing that era in my U.S. history class now. We just finished the Reconstruction Era, and we’re moving into segregation.

It was shocking to me. That was the first time I’d ever encountered that. So, I didn’t like him. I was with my godmother and this man and I got a job as a secretary. And America’s very different from England. In England, everything is sort of laissez faire and, you know, you muddle along here. He [my boss] said, You know, Miss Pratt, this isn’t typed very well. Go do it again. The standards were very, very different and, you know, I wasn’t too accurate with things. So, then I got a telephone call from a very naughty friend of mine who said, Hey, I’ve got us jobs. Leave that god-forsaken state. We’re going to be cooks in a fishing lodge in North Canada. Get your ass up here! [laughs]

Talk about a change – from Florida to Canada!

Yeah, and I went on a Greyhound bus. So you get on the bus and you go across – I mean, Texas is day after day of this flat… I’d never seen anything like that. Never ever. And when you got to various towns, they had these women’s hostels. So you could stay in a women’s hostel and you’d be safe. Which meant a lot. So you knew when you got off the bus there would be a youth hostel or something and you could spend the night there, because it took a lot of time. And then you’d get back on the bus and you’d chug, chug, chug.

How did your friend know about the job?

I’d known her in London and she was just innovative. And youth is innovative, you know? It’s like stepping stones. You step on the first step and suddenly you see the second. And then the third. And, I like the way the Quakers describe it: [Proceed] As the way opens. Because if you can take the first step, even if you’re terrified, something else will appear.

I do think that’s very universal for people of my age … because there’s not a set path or destination. You just sort of have to keep going.

Yeah, you do. You’ve got to have faith. And I think helping that faith is probably a solid home. You know, I did have a solid home in England, even though my parents were pretty upset that I’d gone. But I knew that there was somewhere that was safe. And I think that makes a big difference. I don’t know what it would be like if you didn’t have that.

I worry sometimes that I have too much of a supportive home, that I won’t go out because I love it so much here.

Well, you’re aware of that then. So that you can deal with it. Because you never grow and you never learn if you’re safe all the time. But you don’t want to be stupid either. And I think times are very different now. So just be careful.

So I get to the Canadian border. It’s three in the morning, I’m on the bus, and the customs men come. [In a deep voice] Oh, who do you think you are? they said.

I said, Well, I think I’m coming in to work in a fishing lodge. I have a job.”

[Deep voice] No you’re not. We don’t want you. You’re not coming into this country. You don’t have a visa, or whatever.

I said, Well, I’m a British citizen.

They said, Don’t want you. Out!

So I was a bit stunned. It’s 3 o’clock in the morning. I knew one guy in New York, an old friend of mine, and I called him. And, in England, when you are close to people, often you call them by their last name. He said, Pratt, where are you? I said, I’m on the border of Canada on the West coast. They won’t let me in.” And he said, Well, get back on the bus and come to New York City.”

What about your friend?

She was in Banff waiting for me. So, I told the customs people they had to give me enough time to spend three days in Banff, and they said, Yeah, okay. So I went to Banff to get over the shock with her. And then I went on to New York. Which turned out to be another adventure.

Again, driving across the country in a bus was wonderful. Day after day after day, just incredible. And I always felt safe in the Greyhound buses, you know. Then I remember that someone gave me the name of a man in one of the cities halfway across and said to give him a call and say hello if you stop at that bus terminal. Well, two things happened when I got there. The first was a sort of trolley, you know, loaded with luggage, and on top was a plywood coffin, done up with rope. And – I always remember this – someone had written on it, Help! Let me out! I’m suffocating! [laughs]. Can you believe it!? Very naughty.

So, I’m gonna tell you [the second thing]. I have this number and I thought I’d call. This voice answered and I said who I was and who gave me his name. He said, You stay right there. I’ll be there in 10 minutes.” And he came in a car and picked me up. We went to his house and he fed me and got me back to the bus on time. Now, if you’d done it in England, it would go like this: Brrring, brrring. That’s a telephone. Hello, is this John Sykes?

Yes.

Well, this is Jane and your friend has given me your name.

Oh, how is my friend?

It’s very well.

And did she send a message?

Yes, it was that if I was in a town near you, I should call you.

Well, that’s nice. When you see her, give her my love. Bye.

It’s the epitome of the difference between Britain and America. I tell you that because it’s so deep. Americans: Welcome! Welcome! Come in, we’ll look after you. You’re part of us. We’re here for you! England: Who are you? Very different.

You were very brave on that whole trip! And you were not even taking a train, you were riding a bus!

But everyone did. That’s what young people did then. I felt very safe on the bus but it is risky [today] – I don’t know what the bus system is like now. And there were the odd people to come and sit next to me and try and pick me up or whatever. And there were, you know, these houses [along the cross-country bus route] like some of the religious Salvation Army’s houses that were throughout the country, that were set up to house you. You know I don’t know that they’re there anymore. But [I was] vulnerable and young and innocent.

But as you said, maybe you were innocent, but you were stepping to the next stone. What happened when you finally arrived?

When I get to New York City I get a taxi. And the first thing the taxi driver says is, Wait here, I’ve got to take a leak [laughs]. When I tell him where I’m going he says, Oh, that’s not a very good neighborhood. But it’s where I’ve got friends. So, I moved in with this friend whose name I don’t remember now, and he lived with three other guys. And I thought I’d better get a job. So I was out walking and I see a sign for an employment agency. I go in and say, My name is Elizabeth Jane Pratt.” Now, in England, they would say, “Miss Pratt,” but I’m sitting there waiting and this voice calls, Liz! Liz! So I take no notice, you know? I’m not used to that. And then he finally says my whole name and I go up and tell him I thought I could be a secretary and he asked where I was living. When I told him he said, That’s not a very good neighborhood. I told him, No, I’m fine. I’m living with four guys. He said, Four guys! You’re living with four guys? Now Liz, if you go for an interview, do not tell them you’re living with four guys!

So, he comes up with a job allright. This was a very big law film in New York, he said, and one of the big-time lawyers needs a secretary. Lord Day & Lord. Very big firm. And I get ushered into Mr. Lord’s office. And I’m sitting across this table. He says, “Well, Miss Pratt, I see you are living on the Upper West Side.” I said I was. He said, “Are you happy with your living arrangements?” I said, “Very, very happy!” But I thought, I can’t – I’ll die here. I’ll die. I’ll die. This is not me. So I told the agency and they said, “Well, we’ve got one where you could be secretary in a big Episcopal church downtown.” So I went down there – got hired [clicks her tongue and gives a cheeky nod].

And, it saved my life. The church was very well known – St. George’s on East 16th Street down in the Village at Stuyvesant Square – mostly because of the senior priest, if that’s what you call him – because he was known for wonderful sermons and very good music. And there were two junior clerics, and I was to work for those. But, what it had, which is totally unique, was two brownstone houses. One was for male students and one was for female students. These were for American students coming to the city to work from across the country. So, it gave them a start in the city. And these were beautiful houses. You had to be in on Tuesday night for dinner – we had a cook – because they had speakers come to talk to us. And you had to do one night of community service a week to pay back the community. You could do it anywhere – I went to the Red Cross.

So you moved on from the four guys in favor of this somewhat more cloistered living?

Well it was very free and easy. And I made wonderful friends. It was like God looked after me.

Karma, God, Fate, Kismet. This is an incredible story. How many of you lived there?

Sixteen girls and 16 guys. And so you met each other. We had parties. I mean, really, think about how things fell into place!

I was just going to say: Think about that guy at the appointment agency. At first he sends you to this stuffy office, but you knew that wasn’t for you. Something about you wanted to leave London and Britain, you had this godmother. and then you got on the bus to Canada. And you just kept going.

I think first of all, you have to survive. So I had to get a job. I’m sure there’s luck in there – probably a lot of luck. But why does luck come to someone and not to someone else? And then it’s being able to pick up when you’re given that chance. And I think that is part of the essence of me. That right from the start, there was this sort of rebellion, you know, the scrubbing of the floors and this refusal to go to school and this refusal to be like others.

Like with my job with the two ministers. One was called Ron and he was a very good photographer. One day a Columbia law student named George Krumbhaar called for Ron to say he was doing a paper on the war on poverty and planned to go to Appalachia where the mines were closing and he needed to talk to Ron about how to photograph. And I just said, Well, can I come with you?

Oh, well, whoa, he said. I said it sounds really, really interesting, and I’m new to this country and I should widen my knowledge of it and I probably could help you. So he says he will call back in the morning to talk to Ron about it. And Ron tells him, George, the best thing you can do is take Jane with you. She will see things with a different eye, she’s traveled, she’s experienced, and from a different country.

So George decides he has to meet me before deciding and we go to lunch and he says, Well, can you change a tire? I said, Of course, I can change a tire. I hadn’t a clue. Anyway, off we went in his Mercedes – fancy! And the first evening we’ve got a sort of picnic supper and we’re sitting on a slag heap in the coal mining area and I see this light. Is that someone on a bicycle? But it was a firefly. I had never seen a firefly before! Really, never.

The trip to the West Virginia mining area was one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever done, and it was very useful that I went because I could get people to talk. [Their stories were] absolutely shocking for me. We found towns where the mine had owned the town and paid people in the mine money called script. And when the mine closed, the young people left, the young men went to Baltimore and the young women came to DC, but the elderly couldn’t move and they were caught so we’d find these little towns where people lived with no heating, no plumbing, peeing in the fireplace, children with no shoes. In the jails [there was] straw on the floor.

One day we stopped at a little house up on a hill and we walked up and said, could we talk to you? There was this couple sitting on the porch. The people [in Appalachia] used to chew tobacco and they’d spit but never hit you. [The wife] asked us if we would like to see inside the house. It was an armory! There was nothing but guns. When they asked us where we were going next we told them the name of the village. Oh, they don’t have a sheriff there, they said. They explained that this place once had a sheriff but he was “hard on the boys” and didn’t ease up so he was shot. Well, I think perhaps we won’t go to that place, I said. They said, Oh, they wouldn’t shoot you. They wouldn’t shoot anyone they didn’t know.

He reserved that just for people that they knew! Shocking. If it was bad in the summer, we thought we should go back in the winter. And it was even worse. I mean, I had to throw all my clothes away. The conditions were terrible. This was only five hours from New York! So we came back and he did his thesis of that and then we actually got married. We fell in love [during the research trip]. And so that brought me to Washington, where he worked for the Treasury Department as an economist.

That was your first time in DC?

I hated it. Oh, God, the city was dumpy and a swamp. We lived in an old Black neighborhood in Southeast. We bought a house for $14,000. We lived through the [1968] riots, then we moved near the Cathedral. We bought a house on Upton Street, which I still own. That’s when the marriage fell apart. We’ve been married for seven or eight years by then. He was a good man but I was bored [with that life], to be honest. But I thought, What’s Jane going to do because she didn’t go to school? She’s not going to be a secretary. What am I gonna do?

Someone said to me, Notice what you do and not what you think you should do. And I noticed that I was gardening a lot. So I thought I can be a gardener, I can design gardens. I’ll do that. Someone said there’s a course at GW [George Washington University]. But I thought, well, they’re gonna give you an intelligence test and I’ll never pass it. But I took the test and I got in, but then we did something called percentage slopes. When you do a slope, it can’t be over six degrees. And how do you [calculate] six degrees? I couldn’t do the length over the height over the whatever. So I pulled out, I quit.

I got a job at a plant nursery and asked to learn everything they could teach me. So after a while, people would come in and want a little design. So I’d do a little design. I then asked to join this small contractor, and the [owner] said, You’ll have to work with the crew, the boys. That’s fine. I started doing “take offs” [landscaping design bids] and I did that for about a year. Then I got my first job, a garden in Georgetown. Then I got another one, and another one.

At some point I met Roger Burch, an English gardener. I would work on his jobs and he would work on mine, and he taught me so much. He was a good man. We worked together for about 10 years, but then he just sort of disappeared. But all that time I was building, building. Then architects got to know me and I started to get written about.

It’s all a fluke – it’s all chance! The thing is, you’ve got to take your chances when they happen. I’ve worked for the cream of America. I’ve been flown all over the country [to work on garden designs]. I’ve worked for Rockefellers. I’ve worked for vice presidents. I’ve worked for the White House. I’ve worked for all of them. I try and use what I’ve learned because success is not boom, boom, boom [instant and certain], the way Americans want it, or maybe Brits or everyone wants it. But it’s that we are given opportunities and are open to the opportunity. Never give up on that. It will always be there. There will always be an opportunity.

Tell us about some landscape or garden designs you’ve worked on.

In 2010 I started a conservancy to save Dumbarton Oaks Park [in Georgetown]. In 1950 the park – which is behind the Gardens at Dumbarton Oaks – was given to the [U.S.] Park Service and it was falling apart. And a friend of mine and I started this consultancy to restore it, and it’s going beautifully. There’s a stream in it. It has 14 waterfalls. Bridges, meadows – we found the best meadow man in America who comes in to advise us.

In the Gardens at Dumbarton Oaks Park I designed the Ondine garden. I also did some early landscaping at Glenstone, have you heard of this museum in Potomac, MD? I put the lake in for [owner] Mitchell Rales and his wife. He bought the land I got called in and so I put the lake in. One day this assistant of mine went to put in bulbs and I got a call from someone on the site who said, Jane something really awful happened. They told me the dam went and the lake emptied in about 20 minutes.

Well, when my assistant – she was unflappable, she knew how to deal with [adversity] because she married a man with terrible depression – when she hadn’t called me I wondered if she got washed away, you know? But she answered her phone when I called her. I asked, How’d it go today? She said, I got all the bulbs in. I said, Oh, anything else happen? Oh yes, she said, um the dam broke and the lake’s empty, but I got the bulbs in.

What happens when you design something like that is that the corps of engineers come in and they do the engineering and the building. So I was absolved, you know, I’d just did the layout. So it was never mentioned. But anyway, [Glenstone] has changed a lot since then, but it is beautiful and you should see it.

You did several gardens at the National Observatory?

I did gardens for [vice presidents] Gore and Cheney. I designed the swimming pool garden for Gore. The last one I did at the Observatory was for Cheney when they decided to take down the greenhouses and put in a helicopter pad [which she ringed with concentric circles of plantings, including cherry trees]. But the gardens are redesigned all the time, so it has probably changed.

Do you design according to your style or what the client wants?

It’s never about me. But they’ve got to be fun, unexpected.

An example?

In Georgetown I put in a dead tree and painted it blue. Do you know about bottle trees? It’s hard to find them now because people are so boring now! It’s so hard to find eccentricity!

What’s something that you would have considered challenging?

I think Glenstone was very difficult … and terrifying in many ways. But [the current landscape design] is so different now.

OK, I believe we left off in the chronology of your personal life back in the 1960s. Can we go back to your first marriage, to George Krumbhaar. Did you have children?

Yes, we had two children. My daughter, Ruth Stevens Krumbhaar, is about 57 or 58 years old now. She went to Sidwell Friends School. She and her partner live in San Francisco and have a son at Berkeley. She’s a therapist but is now buying houses – properties – and fixing them up. My son, Frederick William “Fred” Krumbhaar, is two years younger than Ruth. He went to the Maret School. He is a businessman in Boulder and has two children.

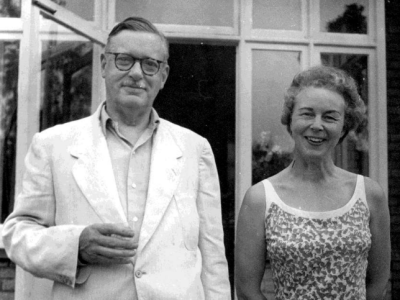

At some point you married again?

I married a man who is very well known, and very pompous. He was a filmmaker and did radio and television, and I couldn’t resist. And so I married him. His name was Rod MacLeish [1926-2006]. He was an extraordinary man, brilliant and very full of himself. But we had a lot of fun, we went all over the world as guests of presidents and what have you. But in the end he got blocked. He couldn’t write anymore. Sometimes writers get what’s called writer’s block. He was totally blocked, but I was being written about [for my landscaping and gardening work]. I had magazines coming to interview me and talk to me and photograph me and then they’d say to Rod, do you want to be in the picture? And one day he just left. he just couldn’t take it. It was incredibly painful. And he would never speak to me again. So I lived through that.

How long were you married?

Probably five or six years. Oh, it was wonderful. And he was fascinating, but it was just one of those facts of life. And there wasn’t anything I could do. So that ended and I kept going and wonderful jobs came. I loved my work.

And then [several years later] I met another man on a job in Virginia. He was an architect, Joe Handwerger [1931-2018]. He was so pissed at me at our first meeting because I said, Well, we could do the lake here and then we could do the prairie there, and he was very upset because he could just see his budget disappearing [into my grandiose vision]. It was terrible.

And then on a Sunday about three weeks later I was at the National Gallery of Art and was walking by the cafeteria and he [Joe Handwerger] was sitting there having coffee, and he said, Jane, come and have some coffee. And that was the beginning of a really beautiful marriage.

I did have this one problem – he’d gone to Harvard architecture school and here is Jane, no education, no training, terribly successful, equally as impressive. He was lovely, but it made it difficult sometimes.

He has since died?

He died [in 2018] in a hospital after hitting his head at home. He was an extraordinary man. He was the one husband that all [my family in England] liked the most. He had wonderful humor. And it’s so unfair he should go out like that.

Did the two of you move to Knollwood together?

No, I moved here about four years ago. I’d always wanted to live here because of the grounds – 17 acres! They have a goldmine here! But when I came to look they weren’t taking anyone who wasn’t military. Then one day they [opened up] to non-military applicants and showed me this apartment. It would have been crazy not to take it! [Jane turns to look at two walls of windows overlooking an old stone country home from last century surrounded by gardened terraces that she designed]. I work on the back terraces where [residents] sit to enjoy the landscape and I did the walkway Knollwood employees use to get from the parking area.

So you are still working in gardens?

I’m still busy. I’m also involved in the Rock Creek Conservancy [a watershed organization protecting Rock Creek National Park]. And I’m working on the rebuilding of the Carter Barron Amphitheatre. We’re starting to raise money for that. I’m not very good at raising money. I’m terrified of it actually.

I’m kind of in awe of the sort of constant theme in your life to just go out and do it – to take the initiative and take the opportunity when it comes. You didn’t really mention – was it constantly scary? Or were you not even thinking about it when you took chances and opportunities?

It was very scary a lot of the time. And I was ridiculed a lot because, you know, [people would wonder] how come you’re so successful? I was aware that I didn’t know a lot, but I worked with wonderful people and I had a good team. I had to survive, I had to make it and be responsible for myself. So I had to get on with it.But I think I’ve been very lucky that I’ve had that inner energy to survive. I think that was a great gift.

The secret is to always be respectful of what you don’t know. You’ve got to be up front about that. And also, sometimes things just don’t work. You just can’t do it the way they want and so you [need to be able to] shake hands and walk away.

Being English helps [wry grin]. I think it was very useful to be English because if you’re English you’re meant to know about gardens [laughs].

Speaking of England, did you sister Anna, live in London for her whole life?

She became a nurse in the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps. She met a surgeon in the British Army, Peter Pitt, and they went to Nepal and they lived in Nepal for years [to provide healthcare for the military members of the then Nepalese royalty].

Then they moved back to England where she lived in a huge, huge house with a moat. There was a little church on the property and the vicar came every third week, which meant if you were staying with them it didn’t matter who you were, what you were – you got your ass to church to make the numbers up and they had a great big bell they rang.

Joe, my last husband, was Jewish and we went to church and after the service there’s a sort of Army chap as we were coming out the door. He gets to Joe and he says, I hope you liked the service, and Joe said, Well, I’m a bit perplexed.

Perplexed?

I listened to the sermon and it said if you hadn’t been baptized, you couldn’t go to heaven. I’m Jewish and I really want to go to heaven.

Oh, come and have some coffee. Pish-posh, he wasn’t really serious about that. You can come.

My final question is, about what’s going on today in society and our country in general. What do you see as the best role for young people like me? And what insight can you give about what young people should be focusing on based on lessons you learned?

The first thing is to be brave, to keep learning, to be open, to be terribly open. Keep getting educated. Keep following your instincts. Love yourself – really love yourself. Trust yourself, and be dignified. There’s a great dignity to life, and to just love people. This is a very difficult time in America, and it’s frightening. But it will change. So get educated and follow your instincts.

But there’s something else. In America, people are meant to be perfect. And in many ways, I fit that picture, but I don’t want to come off as looking like a glory girl. Like most people, I am extraordinary vulnerable, and there are parts of me that has felt a great deal of pain. We ought to be able to talk about it. It’s not all perfect, but that’s life.

END

© Copyright Historic Chevy Chase DC

Oral history interviews may be copied for personal, research and/or educational purposes only under the fair use provisions of US Copyright Law. Oral histories accessed through this web site are the property of Historic Chevy Chase DC. the copyright owner.

Use of these interviews is subject to the following terms and conditions:

- Material may not be used for commercial purposes. Short quotes and references are permitted for instructional and publication purposes.

- Users must provide complete citation referencing the speaker, the interviewer, the date and website with URL address.

- Users may not re-post or link the oral history site or any parts of it to another program or listing without permission.

Questions about the use of these oral history materials and requests for permission should be directed to hccdc@comcast.net or HCCDC, PO Box 6292, Washington, D.C. 20015-0292.