Narrator: Elaine Maria Corcoran O’Malley, age 92

Date of interview: Jan. 18, 2025

Location: Mrs. O’Malley’s apartment at Knollwood Life Plan Community

Interviewers: Amaia Catan, age 16, with Cate Atkinson

Transcribed from audio recording by: Amaia Catan

Abstract

Elaine O’Malley had a secret weapon as a child that she has used to her advantage all her life: She knew how to sit quietly and listen. While the Irish womenfolk in her extended Corcoran family talked as they went about life in Roxbury, MA, she listened and learned about people, about relationships, about what was wise, or not, to say. With this grounding, she managed the tragic disappearance for several years of her father being treated for tuberculosis, her emergence as a mathematician, and the stress onslaught of having six children in seven years.

Born in 1932 and raised in Boston surrounded by a Catholic family with a strong sense of community, O’Malley had a best friend who was a like-minded, mathematically thinking girl. That friend – as luck would have it – introduced her to her future husband. She became the wife of Joe O’Malley when he was still in medical school. He became a physician-researcher who worked on hepatitis vaccines at the NIH and later reviewed new-drug applications. She was a housewife after leaving her mathematician career before the birth of her second child.

O’Malley raised their children with the wits she acquired in those early years of wisdom accrual, and recalls gladly accepted her workhorse mother-in-law’s summer assistance for much-needed respite. As an empty nester, she and her husband traveled to Ireland and countless other places with Elder Hostel, and she volunteered at the Smithsonian. And then one day she found herself with a full-time job as a licensed DC tour guide – a serendipitous venture that she enjoyed for 20 years despite having never imagined doing such a thing previously.

O’Malley, who is now 93 and lives in Knollwood Life Plan Community, moved to DC in 1957 for her husband’s NIH job. They were married for more than 60 years at his death in 20017. Her eyes shine when she talks, an ever–present smile framing most words. She is upbeat and positive. Even the acknowledgement that she has lost three of her six children is recounted with a note that she has been a blessed woman. “I would like to be remembered as someone who is grateful,” were her parting words at her oral history interview.

Amaia Catan:

This is Amaia Catan interviewing Elaine O’Malley. We’re here in her sunny apartment in Knollwood, where she has lived since 2014. I know from talking to you earlier you are a mathematician, the mother of six children, an “accidental” DC tour guide for 20 years, and the spouse of a physician-researcher who worked on early hepatitis vaccines. I wanted to start by asking where and when you were born?

Elaine O’Malley:

I was born in Roxbury in Boston, MA, on the 15th of July, 1932, to Mary Grace Cleary Corcoran [1897-1974] and James Lawrence Corcoran [1899-1973]. I have a younger sister, Mildred Corcoran Feloney, who lives in Needham, MA. I lived all my life in Boston until I came to Washington with my husband for his work at the National Institutes of Health. This was his choice of where he wanted to be, but I was very happy to come. We had been married for about three years when we moved here – he was finishing up the last two years of medical school and an internship, so that kept us in Boston. But he knew, almost from the time I think he was in college, that perhaps he wanted to go to medical school, and that he wanted to do research rather than to have a practice. So I knew well ahead of time that we probably would be leaving Boston and coming here to live, and I was very fortunate, because I really grew to love Washington very, very quickly.

That’s a pretty adventurous thing – a brave thing – to move from the place you were born and raised to a new town. Would you describe yourself as an adventurous, curious person?

I believe that I was a curious person. My guess is that most people wouldn’t have described me in that way. I was somewhat shy or reticent while growing up. I think it stemmed from the fact that both my parents were in education. My father was a teacher of mechanical drawing at the high school level, and my mother worked as a secretary in a school. I think the result for me – and less for my sister, who is 20 months younger – was I thought that meant being a good girl all the time and not getting into any trouble. I really was often curious about things, but I think I devised ways of satisfying my curiosity that were not typical of, you know, asking questions or looking at things or wanting to have some kind of adventure. I was eager to know as much as I could about things and why and how they operated, but I tended not to do it in a direct way. One way was to listen when other people were having a conversation. That didn’t mean I didn’t talk, I just found that you learned a lot of things if you could sit quietly and listen.

My sister, Mildred, could never have done that. She couldn’t have sat still and listened if her life depended on it. In school, she always had a group of close friends, and by high school she would refer to them as her “gang.” But gang, I think at that time, would have a totally different meaning from what it brings to mind now.

What did you learn while listening to people?

Whatever people were discussing. I wasn’t spying because people were talking in an open way with each other, my mother with her friends, what was happening with whom. But I do think that sitting and listening satisfied my curiosity in many ways. I started doing it very young. My mother and my grandmother [Ellen Augusta Rosenworth 1866-1940]– my mother’s mother – had lived in the same part of the city their whole lives and knew a great many people – knew every teacher that I ever had, from kindergarten through eighth grade. I would sit and listen to these very pleasant adults, and I learned more about Roxbury and Boston, and the people who lived there, about books and reading and education, and I learned a lot about my family. I realized quite young that my mother seemed uncomfortable around my father’s family. They, too, lived in the Boston area. They lived in a town adjacent to Boston. It was called Brookline. Parts of Brookline were a very affluent suburb – now, and when I was growing up.

My father’s father [Lawrence Corcoran 1865-1931] was a foreman of the Parks Department in Brookline. So they were not affluent. Though certainly, he was paid a wage, and they were able to raise a family of six children and send most of them to college. So there were a lot of advantages to the fact that he had a very steady job. When I listened to my mother talk, I sometimes found out things, I could see what her attitude was. I knew that she tried very hard to get along with my father’s family. We saw them a great deal because we lived so close to them.

My mother met my father skating in a park which the town of Brookline apparently arranged [in winter] to have flooded so the children could ice skate on the pond. They were teenagers. My mother was born in 1897 and my father in 1899. The First World War started when my father was about 18 or 19 years old, and he joined the Navy.

Where was he stationed?

He was on a transport ship that would sail from Boston to Europe and pick up the sailors or the servicemen who had been involved in fighting during the battles, and then they would bring them back to Boston. My father liked to talk about things. He exaggerated things sometimes. So you could never be very sure, right? I know that he talked about the fact that he was in Paris. And I thought that was, you know, imagine, that this man, my father, had been in Paris! I thought that was extraordinary. Of course, that makes perfect sense. There would have been free time, so he probably did spend a little time in Paris. That was a good question. I haven’t thought about my father and his story about Paris for a very long time.

I find it interesting to listen to my parents interact with others because as a kid, you only think of your parents as your parents. But when you see them interact with their best friends or with their siblings or with anyone else, you realize that they’re not just your parents.

I’m glad you mentioned that, because I think that’s exactly what was happening to me as I was growing up. And it really also ties in with the curiosity, in a way, because I certainly knew that there were things about my parents’ life that wouldn’t be appropriate for me to ask them about it. For example, I might have known about their attitudes towards certain people just by listening to their conversation, but I would also realize that it would not be a good idea to ask my parents about it. It also wouldn’t have been a good idea to have shared anything that I realized about my parents with anybody else – friends or people who might ask me questions. I knew that I had a very good sense of privacy when I was growing up.

Tell me about your school years. I understand you graduated from high school in 1949 then went to college in Boston where you graduated in 1953.

The grammar school I went to was an all-girls’ Catholic, or parochial, school because it was sponsored by the local parish where we lived. When I was in the fourth grade, a part of Roxbury that included the street where my grandmother and my mother had both been born, had actually been purchased by the political powers who ran Boston. They had purchased that land because so many people were finding it difficult to find affordable housing. A great many of the houses in our parish had been torn down, including my mother’s family home, and affordable housing was placed there. [Her grandmother, by that time crippled by arthritis, came to live with them after using eminent domain proceedings to take her home]. That brought more and more children into the school that I had gone to from first grade.

In fourth grade, I made a friend among those new students named Mary, and I can show you her picture, because I have one here, and I’ll tell you more about Mary and my relationship, because it affects my life very greatly.

Probably because my parents were educators, I knew that doing well in school was very important, so I tried very hard, and I was very obedient. The way people often expressed it, was that Oh, Elaine was very smart in school. So smart that Elaine made a friend of Mary, one of the new girls who had come into the school, because Mary was very, very smart. One of the things that I doubt very much they do in schools now, but the principal of this Catholic school liked to come into a class and give problems in mental arithmetic: multiply two by two, add four, subtract one. Mind boggling.

Thank God they don’t do that anymore.

I noticed, because they did things like that in most classrooms at that time, that Mary was just as smart, if not smarter, than I was, and I liked her. We got along very well and we both were quiet and less apt to cause trouble in the classroom by, you know, children passing notes to each other or things like that.

Massachusetts has a history of being a pioneer in education. Did you think your schooling was of a high quality?

That was probably a pretty good school. We went because it was the school that was closest to where we lived, and it was also attached to the church that we attended. In the eighth grade, a choice had to be made about where you would go to high school. My parents made it clear to me that they would like me to go to a particular high school in the city of Boston called Girls Latin School [and not] to the high school that was connected to my grammar school. Academically, it had a very good reputation and I knew from the time that I was probably in fifth or sixth grade that my parents wanted my sister and me both to go to college.

It always pleased them that I did very well in school. A lot of it was due to their help and their encouragement. I was really quite aware at that time that not every girl had that same kind of encouragement that I did. That made sense, that they wanted me to go to Girls Latin School, and I was perfectly willing to do that. But two years later, when my sister was in the same position, she said she wanted to stay with her friends, and they wisely went along with it. And it worked out very well.

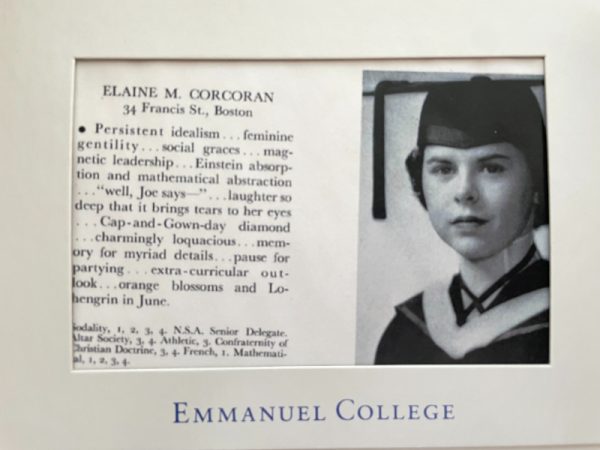

Interestingly, when I graduated from high school, I won a scholarship to a local college, Emmanuel College. And when my sister graduated from high school, she also won a scholarship, and we ended up going to the same college.

What was your relationship with your sister like?

With my sister? Oh, my goodness, you know, I think it was a good relationship because love of family was very important. But I also knew that she wasn’t a perfect person, as I wasn’t, and I knew that sometimes it was kind of a nuisance. I never, of course, had to take care of her literally, but it was understood that I would kind of watch out for her if we were just out playing, or if we were going to go to a movie with other children or something. You know, tak[ing] care of my sister was a part of my upbringing. That was just a nuisance sometimes, but we had a good relationship. She went on to her high school. I went to Girls Latin School.

By mid-grammar school, there were rumblings of World War II. Were you aware of the conflict on the rise?

Yes, I was. One very strong memory I have was listening to the radio in the front parlor, which was one of the few forms of entertainment we had, and I heard the announcement of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Wow – it was unlike almost anything else I had ever heard on the radio, the excitement of this! I remember running out so I could tell [my family]. War was declared within a day or two, I think. And then war became a part of our life because it was obviously such an important thing to have happened to our country. And I think from the news, we knew enough about the war that we knew there were enemies that wanted to do a great deal of harm to the people of my country.

I remember that there would be collections of newspapers or metal objects so that they could be converted and used as weapons of some kind. We prayed frequently, in places like churches, schools, all over the country. We prayed for the safety of these young men who were drafted because they must. My eighth grade teacher at the time had us write letters to men in the service. She had particular people that she wanted to get the letters, and there was somebody named Carl. I didn’t think it was unusual, then, but I realized later in life that was rather a strange thing to do.

I don’t know if Carl was a relative of hers, a nephew, perhaps, or somehow or other, but she had Carl’s military address, and there would be a part of each day, probably near the end of the day, when all the other work was done for school, that we would write letters, and then she would post them. So I wrote letters to “Dear Carl” while I was in the eighth grade. See, I graduated from the eighth grade in 1945 from high school in 1949 in college 1953.

So because of this teacher and my writing to Carl, it helps me to remember dates. If I said this to a group of people – women here at Knollwood – that I graduated from eighth grade in 1945 they would ask how I can just remember those numbers. It’s as if they are burned into my brain somehow. Oh well, doesn’t everybody know what year they got out of eighth grade? [laughs]. I think a lot of people do, but a lot of people don’t remember numbers easily.

I can remember telephone numbers for a long time. But we did not have a telephone for a long part of the time while I was growing up. They were sort of rationed out [during the war].

What did you use instead to communicate? It’s difficult for me to imagine not having a smartphone.

Oh, you wrote letters. Anyway, believe me, you found ways to communicate and to share information.

What did you study in college? You said you were good with numbers.

I was a math major. I had always been good at math; it always made great sense to me. My father was a good teacher. He taught me that you should never be afraid of numbers. Numbers are so important, so useful. So I had learned quite early in life that numbers were kind of fun, even.

When my sister and I were adults, something came up about addition and I [said] I couldn’t see any reason why you wouldn’t like addition, you know, because to me, it was so easy. She said, Well, I just don’t like to do things like add nine and six. And I said, Well, that’s 15. And she said, Yes, but how do you know that? How do you know that just using a nine? I explained that you use a 10 and subtract one from the other number. She looked at me and said, I never thought of that. She had every advantage that I did, and she was every bit as clever as I was, but she did not [understand math].

[Nor] had she ever learned to be a good girl. One time, when she was probably in sixth grade, she was supposed to be getting a new dress for some special religious event. My mother, who had actually learned to drive even before she was married, was going to pick up my sister at school in our car. So she came up to my sister’s classroom to get her. My mother was always in a hurry – she always had so many things she needed to do and to get done – so she came up to collect Mildred to go get the dress for her confirmation. And the nun said, That girl does not deserve a dress.

The nun probably thought that she was doing Mildred a favor to let her mother know that she didn’t behave well in school. The nun told my mother that Mildred had passed a note in school. Well, my mother told the nun, I hope she never does that again, and I will tell her not to.

Mildred loves to tell the story. She sat down in the car and started crying. Mamma said, What’s the matter with you? Mildred said, I’m not going to get a dress! whereupon my mother responded, I don’t have to do everything that that nun says.

I think the nun had irritated my mother by the way she handled the situation. And my mother, although not a teacher herself but because she was married to a teacher and she had worked in education, I think she knew that you don’t embarrass children in front of their parents.

As a math major in college did you ever feel, as a woman, you were treated differently than how your male counterparts were treated?

I don’t think I ever did. But again, I think this is basically the way I was brought up. I knew from the time I was quite young that I was a very worthwhile person. I understood that I should never be influenced by what other people said or did, that if I ever had questions to come to [my parents], and they would be glad to talk to us. Listening to what other people say or letting their opinions affect your life is not a good idea. I didn’t realize fully how valuable that was until I was an adult, of how wise they were in the way they brought us up.

There was something very unusual that did happen in our family while I was growing up. Do you mind if I take a moment?

Of course.

When I was six or seven years old, my father was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and the law in Massachusetts at that time required him to be taken out of his home. He was sent to a sanitarium, and one of his lungs had to be removed. While he was there under treatment, he was actually gone from our life, oh, I would guess, for about three years. For a long time I never knew where he went or when he left or returned.

A lot of this had to do with the secrecy that surrounded tuberculosis at the time. It was a disease that can be transmitted very easily, and there was such fear connected with it. The chances were very good – and I didn’t realize it at the time – that you really wouldn’t live very long. He was gone until I was in about fifth grade or so. I didn’t really realize until long after, that in many ways both my sister and I were blessed by the fact that it made them so much stronger to have had to deal with this. Because basically my mother may have been able to have saved a little bit of money while my father was working, but I don’t think they would have saved very much. And I really think that what my mother had to do at that point was support her two children. The three years my father was in a sanitarium my mother was not allowed to visit or see him. I don’t even have a clear idea of what, if any, communication they had with each other.

I can only imagine how difficult that must have been.

It was. It’s actually an extraordinarily unusual memory. I can remember it very clearly. It was a major event in our lives. I can remember sitting with my mother and father – I think my sister wasn’t there because of her age – and my father telling me he had to be away for a while. This is actually what my mother said all the time, that he was gone, that he would be gone for a while, a long while, perhaps, but that I should always remember. I should never think I didn’t have a father because I knew about God from going to Catholic school and church, and you always have a father, because you have God. God will always be your father.

I don’t think I really absorbed it completely by any means. I knew something very serious was happening to me at that age. And I think I wondered about it for a long while. And actually it was probably the best way [for my parents] to handle it, and they, for the most part, did very, very, very well. I can remember that somebody, probably one of her daughters, brought my grandmother [Catherine Kelleher Corcoran, 1869-1949] to our house so she could see my father before he was to be hospitalized. I think I remember it because my grandmother had never come to our house any other time. And I thought that was such a strange thing, but I knew it was connected with whatever was wrong with my father, and I knew that this was a serious occasion, just by the sadness of all the people involved, my mother, my grandmother, my aunt. But that’s sort of where, in a sense, I think I was curious.

I was much more curious than my sister ever was about where my father was and what was happening. But I also knew that this was a very tough subject for my mother to handle, so I did not press her about it in any way, and that was probably just a wise, wise thing to have to have realized for that age.

You have since learned where he was taken?

I did. A well known sanitarium in a small town in Massachusetts called Rutland – one of the first places that was successfully able to treat patients with tuberculosis. And I did not come upon that fact until [after reading up on the treatments at Rutland years later, including the use of streptomycin]. Had my father taken ill even 10 years earlier, he would not have survived.

Basically, I did not even know he had been treated for tuberculosis until I found clippings from newspapers my mother kept [when I was a teenager]. It stated that my father was hospitalized with tuberculosis. I remember thinking, Oh, my goodness, I never knew that. He never said the word. I think we – both Mildred and I – were specifically told that if somebody asks where our father is, that it’s not a good idea for other people to know that much about us, so just be very careful and don’t give out a whole lot of information.

My mother could be very direct. She probably said to tell people it was none of their business. On both sides of our family, either the parents or grandparents were immigrants, mostly from Ireland. My maternal great-grandfather was actually from Bavaria, and my mother was always very proud that she had both Irish and German ancestors. She said that was much better than having all Irish ancestors. I never knew why it was much better, but she said it was so. I thought, well, you know, okay, I’ll buy that.

How did you meet your husband Joseph Paul O’Malley?

Remember my friend Mary from fourth grade? Yes, okay, Mary went to a different high school [than me] but Mary also won a scholarship, like my sister also did, to go to Emmanuel College, where I also had won a scholarship. I had stayed friends with Mary all through high school. After our first year of college, Mary and I both had part time jobs in one of the Boston Public Libraries, in one of the branches, as they called them. So one Saturday morning, we were both at work shelving books and she said, I’m going out tonight with my cousin’s roommate. I had met very few of her relatives, and she said her cousin goes to Holy Cross College. She said she’d been fixed up with his roommate and would I go out with her cousin so she could meet his roommate? It was Sept. 16, 1950.

So I went home from work, had my lunch, told my parents that I was going out that evening with Mary and friends of Mary’s, and they knew Mary very well by this time. So they said, All right, so I walked to Mary’s house and she met his roommate, his name was Ted, and I met her cousin, whose name was Joe. And my strongest memory about that whole evening was that we went to a place that had a dance floor and a place where you could get a coke or something to drink. He told me jokes through the entire evening. It was probably, you know, maybe two, two and a half hours at most. I heard every corny joke ever heard in this life. I thought, this boy doesn’t do much … anyway, the evening passed and we started our sophomore year. When it came time for the fall prom, Mary asked if I was going. I told her I’m not dating anybody so I didn’t have anyone to ask. She said, Why don’t you ask my cousin? She was dating Ted, but I said, I don’t think so, I never heard [back] from him. She said, So what, what difference would it make? I knew that my parents loved me to participate in everything you could participate in. I thought about it, and I said, Well, if you get me his address I’ll write a letter, so I did. The sophomore prom is coming, and Mary has invited Ted, and if you would like to come, consider yourself invited. Best wishes. And I got a letter back. It was actually a very nice letter. I thought, Well, he’s not quite as bad as I thought. I didn’t think he was bad – I just thought that it was so strange that you meet somebody for the first time and all you do is tell them jokes. And somebody said to me, You know, maybe he just didn’t know what else to say. You know, he had never met you and he didn’t know anything about you, since that was just something he knew we could do was tell jokes. I said, Well, maybe, who knows. In any case, that was how I met him. We had a nice evening at the sophomore prom.

That Christmas, he was staying with his aunt and uncle who lived not far from me and he called and asked if I would like to go to the movies. We had started writing letters by that time and his were very well-written letters. And we went and it was a very, very nice evening. I wrote in a [diary] of some kind, Much to my surprise, he was very intelligent.

I was invited to his [spring 1951] college graduation and that was where I met his parents for the first time. His father [Joseph O’Malley, 1895-1981] had been a Boston policeman for a while, but gave it up after he met Joe’s mother [Anna Cornwall O’Malley, 1896-1994], who was running a little store [in Jamaica Plain]. Later, she bought and rented out houses. By the time Joe was in college his parents had bought a little house in Florida and they would go there for the winter and then come home for the summer. Joe never wanted to go to Florida, which is why he was in Boston that previous Christmas.

When did you learn Joe had his sight set on working at the NIH?

I think I knew from the time we first started dating that he organized his life in a very definite way. So I was never surprised. He had finished two years at Harvard Medical School when we got married in 1953, after I graduated college. And our first three children were born within a very short time.

Our first child was a boy, but I had incorrectly intuited it was going to be a girl.

And I was flabbergasted. I can remember saying to Joe, Oh, God, what shall we name him? And Joe in one of his finer moments said, I think we should call Jim, after your father. Joe greatly admired my father. He loved his father, but his father had been a Boston policeman, and they are known for their short tempers – and his father had one. That’s perfect, I said. I wish I’d thought of that myself. So we named him James Edward O’Malley – Edward for my husband’s college roommate who had died the year before. He was born in May of 1954.

In August of 1955 my second child was born, and he is a junior. So he was Joseph Paul Jr. In September of 1956 I had my third child, and his name is Stephen Michael O’Malley. And by that time, I think I was absolutely convinced I would probably only have boys, no matter how many children I had. But our fourth child is a girl, and her name is Julie Elizabeth, now Smith. She was born in October of 1957. My son, David Andrew, was born in April of 1959. My youngest son, Philip was born May 31, 1961 – six children in seven years. Wow, there’s a lot. I would not advocate it [laughs].

Did any of your children inherit your facility for numbers?

No, none of them seemed to be very interested in that [laughs].

So six children in seven years – how did you manage?

I had a great deal of help, which was fortunate. Probably the most help, in many ways, was really from Joe’s parents. His mother in particular. I wish I had interviewed her at some point, because her life was extraordinary in many ways. She was born and raised in Ireland. Her father’s name was Ralph Cornwall, and Ralph Cornwall had two marriages. His first wife gave birth to, I think, six children. And then Ralph Cornwall’s second wife had nine children, of which Joe’s mother was one. So he was the father of 15 children. And she did a lot of the washing for the family, when she was still a school-aged child. She did not look on somebody having six children to take care as someone deserving pity!

She probably didn’t have much formal education at all. She came to America when she was about 25 years old, got a job in a shoe factory. She saved money as much as she could and eventually had enough saved to rent a property and open up this little store. She sold canned goods and cigarettes and candy and the kinds of things that someone who didn’t have a car could run and get milk and bread for dinner. The store had an apartment behind it. It was only about two or maybe three rooms at most, and one of the rooms had a crib, and that was where they kept the baby. And they lived behind the store.

Joe’s father left the police force before Joe was born. He actually met Joe’s mother because part of his job was to police that little neighborhood area where the store was and she was running the store. Eventually he married the lady who owned the store. I don’t know at what point they actually stopped running the store, but it was somewhat connected with the start of the Second World War. She had worked hard to get the store and she ran it pretty successfully. And there came a time when she realized that you could buy a house for much less than what they were worth due to the war and the situations that were created. Housing was scarce. Everything was scarce. So she ended up actually owning five houses. When I met Joe, she was buying houses and renting them out as flats that several families would live in. I didn’t know anybody who looked at things the way Joe’s mother did. Joe would say you weren’t brought up in Ireland, one of 15 children. He wouldn’t mean it cruelly, but his point was well taken. I had no idea what it was like to have that kind of ambition and to work that hard.

I know that my mother worked, but I knew that she had summers off, and

we took vacations. And Joe had not been on a vacation because, well who would watch the store? It was a whole different kind of a lifestyle. And frankly, I wondered what she would think of me. [When I met her] I had finished two years of college and I didn’t have any great plans for the future except that I knew I was going to marry Joe O’Malley. But she was extraordinary. She could be very sarcastic. She did work very hard, but she was good to me, and she was very generous.

So the point of all this blather is that actually our first child was born in May of 1954 and I had actually worked until almost the first of May that year, but it was a good job. I was a mathematician at the Air Force Cambridge Resource Center, so I was sitting at a desk most of the time, and I worked until I had the baby. Joe and I were living in an apartment in downtown Boston, very close to the medical school, and I said something to Joe about something I was going to do. And he said, What about the baby? I said, Well, what about the baby? I said, We’ve got the baby. I’m not going to give him away. And he said, My mother said she wants to take care of him. And I was rather stunned that anybody would even volunteer something like that. But he said she would really like to. So after my three-month leave of absence, we arranged for that. They would drive every day from where they lived to our apartment, probably a 15 minute drive or so. Joe’s father would sit in the parking lot, in the car, and she would come up to our apartment, and we’d have him all tucked up in his blue snowsuit or whatever. She would take him and care for him until I was home from work, and then they would reverse course, get in the car again – the baby and Anna and Joe – and drive over to the apartment and give us back our baby.

It wasn’t an ideal situation, and I would not recommend it. I think that it was a difficult decision [for me] to make. It was good financially, but I missed [the baby] terribly. I really resented the fact that I could not take care of my own child, but I know he was well cared for, safely cared for. I don’t think he even got a cold that whole winter she took care of him. And they loved taking care of him. They did not have a warm, fuzzy relationship, his parents. They argued between themselves. You know, I think that there were a lot of differences in their upbringings and in their views of life. But they loved all my children very much. I quit work a few months before my second child was born and I didn’t go back after that.

You moved to Washington, DC, when?

Now, this shows you how much Joe and I weren’t always as smart as our educations might have you think. We thought we’d just come down, find a house, buy it, and move in. In the long run, it worked out pretty well. We did see a house [on Kensington Parkway in Kensington, MD] we liked, and we bought it. So for the first time in my life, I owned – or we owned – a house. My parents always lived in rented houses. We lived in that house from 1957 to 1988, 31 years, before moving to Cedar Lane in Bethesda until 2014, when we moved here to Knollwood.

I liked that whole idea [of homeownership], but I had never taken care of a house. My mother, even though she worked, decided that rather than teach her children how to cook and clean, it was easier to cook and clean and tell your children to just go do their homework. That was pretty much what she did. I was unused to taking care of a house and found it very hard because I had three children. We moved in on the first of July 1957 and my daughter – our fourth child – was born in October of that year.

And again, in times like this, Joe’s mother and father would get in their car and drive to Washington. He would drive; she never learned how to drive. That was about the only thing that I could do that she couldn’t – I’m not kidding. She would get here and start the washing machine, put something in the oven. She was amazing. I resented it very much at times, but I was also grateful too for the help.

From then on, once we got to the end of June, we would take however many children we had – four, five, or six – and load them in a microbus – a van that could hold about nine people – and drive to Boston. And some of the children would stay with Joe’s mother and father and I, and whatever children were left over from that would stay with my mother and father. I would stay for a good part of the summer, which was really wonderful for me.

And even though I had a cleaning lady once a week I didn’t have a whole lot of help. And truthfully, Joe was an only child. He loved his children, but he had never taken care of a child. So he wasn’t a huge help. One good thing was he always knew what to do if there was something wrong with them. He’d gone to medical school. But the undertaking was very difficult for those first few years, and going away and having a long respite during the summer was the only thing to do. I know he missed us, he missed me, he missed the children and having them around. But I think he was very practical, like his mother. This made sense. This made sense because we had childcare, and I had a chance for help that otherwise I wouldn’t have. And so we got through it. We were married for 64 years.

What was Joe’s work at the NIH?

Basically, he did a lot of research in hepatitis vaccines, investigating new drugs. I don’t know what his title was at the time. Then, when he had been here about eight years, he came home from work one night and said, I think I’d rather do something else. And I said, What do you mean? He said, Well, I was thinking maybe I’d like to go to law school. And I thought, Are you out of your mind? You know, you have these children. We have this house. In my mind this did not make sense. And it didn’t, to be truthful. However, he never went to law school, because around the same time that he was thinking of leaving NIH and his research in hepatitis, a new role was created within the Food and Drug Administration. And Joe was working at the NIH as a commissioned officer of the U.S. Public Health Service under the FDA. Because of that, his role was to be a new-drug investigative officer. So anytime a new drug came up for approval, a committee of scientists and physicians, which included Joe, would review the research before it could be licensed. So that was the offer and thank God, he thought it sounded interesting. And I think it did interest him for just about the whole time that he stayed in the Public Health Service. He did retire after 22 years of duty. He could have retired after 20 years, but he did a couple more than he needed. After that he went to work as the medical director for the American Red Cross.

And, by that point in our lives, our children were by and large educated. So we had some free time, and we both realized we loved to travel, and we did a lot of traveling over a number of years. It must have been around 1978 when he retired from the PHS, as we would have been married for 25 years and Joe said, Well, what do you want to do for our 25th anniversary? And we thought about it, and we thought traveling to Ireland would make sense, because most of our ancestry is Irish. So Joe said, All right, let’s do that. Let’s go for a month, and you plan the trip, and I’ll take the time off. And I got a whole bunch of travel books about Ireland, and I already knew a fair amount about Ireland, because we had been a few times, and I loved it, and that’s why I wanted to go back. So we took a driving trip and stopped at all the places we wanted to see.

It was really from then on we discovered what they called Elder Hostels, and that really appealed to Joe, because it struck him as financially so sensible because your lodging and your meals and a great deal of your entertainment is provided for. We’d go for a short period of time, maybe a week or 10 days. We did a huge number of elder hostels, probably to about 22 countries, which isn’t a world’s record by any means, but still.

And fortunately, Joe did not mind all the driving. I could never have – I would never have dreamed of trying to. I would do all the planning and he was happy with that. Joe never considered I knew how to drive very well, but that was his only flaw.

Tell us how you came to become a DC tour guide.

I got into it by accident. I had been doing volunteer work at the Smithsonian American History Museum, giving tours of the First Ladies Hall. I really enjoyed that because there was so much history connected with these women. One of the fellow docents was thinking about becoming a paid tour guide in DC and asked me to tutor her, as she knew I knew a lot about Washington. And in the course of helping her, my friend suggested I go with her to take the [DC licensed tour guide] test to see if I’d pass. I loved volunteering at the museum but I said, All right, I’ll go with you. We both took the test and passed. I got a 70, which I did not consider a very good mark, but apparently, most of the people who took the test knew much less about Washington than I knew. I wasn’t intending to use it, but by pure chance the mother of one of my children’s best friends called me up to say she was working for a company that hires tour guides to get on buses and drive around the city. She knew I gave tours at the museum and asked if I’d be interested. She said you just speak into the microphone, tell them about everything that you’re passing. She said, Why don’t you just try once or twice to see if you like it? I found out that I really liked it. I tried staying on and doing tours at the museum, and I found that was too much of an effort. If I was going to be good as a licensed tour guide, then I had to be well rested, so basically, that’s what I did. I started doing tour guiding full time, and I did it for about 20 years, in the 1980s and ‘90s.

I did enjoy it. People are very appreciative of what you have done. You know you’ve made their trip meaningful for them in a way that a guidebook would never be able to do it. So it’s a very rewarding job in that way. In addition to which I had never done a job where I was paid tips. I wasn’t doing it because I needed the money. I was doing it because I loved the job. It used to make me chuckle when I’d see people come and press money into my hand, I’d get a kick out of it because that’s how they’d show their appreciation.

You mentioned that your sister lives in Needham, MA. She has also made it into her 90s! What did she end up doing with her education?

She became a teacher. She has memory problems now.

And your mother-in-law Anna. She also lived a long life.

She was nearly 100 years old when she died in 1994. After her husband died, it was decided she should come here to Washington, DC, to live. But she didn’t want anyone telling her what to do, so living with anyone in the family proved to be too difficult. So eventually we found a facility that she got used to.

Bring us up to date about your children and whether or not you have grandchildren.

I have one grandchild from my daughter Julie, and that granddaughter has two children, so I have two great-grandchildren. They all live in California.

What career paths did your children take?

Julie graduated from Georgetown Dental School and she and her husband Randall Smith, who she met at Georgetown, shared a dental practice in Anaheim for years. Stephen, our third child, was an accountant. David [fifth child] was a veterinarian. Joe Jr. [second child] a real estate agent [who now lives in South Carolina]. The closest thing to describe Jim, my oldest son, is an entrepreneur. And that leaves my youngest one, Philip, who is in real estate [in Greenbelt, MD].

[Later, in a follow-up phone conversation, Mrs. O’Malley was asked to talk more about her children. The interviewer had since read the 2017 obituary of Mrs. O’Malley’s husband and learned he had been pre-deceased by two of their six children, events that had not come up during the initial interview. Mrs. O’Malley was asked if she would feel comfortable talking about those losses. She paused and explained that she did not bring it up in the initial interview because it involved much sadness, and her overall outlook in life is one of being grateful for her blessings. But she said she didn’t mind talking about it.]

I guess, to have brought it up could have reduced me to tears… because I must also tell you that another one of my children died since that obituary was written – my son, my third child [Stephen Michael], died in 2021. He was found in his home after he couldn’t be reached. An autopsy showed it was cardiac related – I’m not sure what the medical term was. Before my husband died, Stephen had decided to retire [early] from Montgomery County [Department of Finance]. At the time, my husband had a fair amount of dementia. Stephen was unmarried, and he said retiring would give him more time to help us out. Well, he was always a helpful child, but he was a godsend to us in those years.

And your son David, who died in 1993 was only, what 34 years old?

A young police officer came to our home quite late one night and advised us it would be better to sit down. He informed us our son had died in Columbia, MO. David was a veterinarian and he lived in Bethesda but he was doing an internship in Columbia. He collapsed and [died of a heart condition] while outside searching for his dog, or maybe it was his cat, who had gotten loose. My husband had to fly to Missouri with our eldest son to identify him. He could never talk about it. Like many men, he did not believe in showing his emotions.

And your eldest son, James, how did you lose him?

Around Christmas in 2007 Jim was diagnosed with multiple myeloma. His marriage had ended several years before and he had met a wonderful woman, and was just waiting to marry after her son graduated from high school. He had started feeling quite ill and my husband told him he needed to go in for tests … he was diagnosed in the hospital but was told [nothing could be done] and he died in June [2008], only six months later.

How have you managed this much grief and remained so even-keeled?

Considering all the important things in my life that I have already mentioned, I must say that my life is filled with enormous blessings. I lost three out of six children, but what occurs to me is that I’ve had a life of great blessings. I would like to be remembered as someone who is grateful.

That sounds like a good place to wrap up. Thanks so much for sharing your life story with us.

This has been a great pleasure for me, a great pleasure. Thank you so much.

END

© Copyright Historic Chevy Chase DC

Oral history interviews may be copied for personal, research and/or educational purposes only under the fair use provisions of US Copyright Law. Oral histories accessed through this web site are the property of Historic Chevy Chase DC. the copyright owner.

Use of these interviews is subject to the following terms and conditions:

- Material may not be used for commercial purposes. Short quotes and references are permitted for instructional and publication purposes.

- Users must provide complete citation referencing the speaker, the interviewer, the date and website with URL address.

- Users may not re-post or link the oral history site or any parts of it to another program or listing without permission.

Questions about the use of these oral history materials and requests for permission should be directed to hccdc@comcast.net or HCCDC, PO Box 6292, Washington, D.C. 20015-0292.