From Typist to Acting Chairwoman: Ana Steele Clark’s 33-Year Career at the National Endowment for the Arts; “A Beautiful Life”

Narrator: Ana Steele Clark

Date of interview: July 10, 2024

Location: Chevy Chase House, 5420 Connecticut Ave. NW, Washington, DC

Interviewers: Charlie Martin, age 17, with Cate Atkinson

Transcribed from audio recording by: Charlie Martin

Abstract

Ana Steele Clark was born in Niagara Falls, NY, in 1939. Her family soon moved to New Castle and then Wilmington, DE, where she resided until college. Clark recounts growing up in a household with both Puerto Rican and British influences, her remarkable educational performances in an all-girls Catholic school environment, and the emergence of her passion for theater.

After graduating from Marywood University in 1954, Clark moved to New York City to pursue an acting career. Clark worked numerous part-time jobs to sustain herself, as the entertainment industry was increasingly competitive. Eventually, Clark realized that a career in acting wasn’t for her, and she looked elsewhere for work. Her father recommended she join a newly emerging government agency called the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA).

Clark started working in the NEA in 1965 at 26 years old, and she would spend a riveting 33 years with the Endowment. During her time, she progressed from being a clerk-typist to the Acting Chair in 1993, met her late husband John Steele, advocated for arts of all varieties at a national level, and found a warm and strong community.

Clark retired in 2001 and she and her husband went on a road trip around the country, employing the connections she made during those years in the NEA, seeing the fruits of her labor. For most of their married life they lived in an apartment condominium in Foggy Bottom, DC, which Clark still owns. Clark suffered a hip injury in 2023 and moved into the Chevy Chase House, an assisted living facility in Chevy Chase, DC, where she currently resides and receives physical therapy. Clark ponders on her decision to stay in the assisted living facility or move back to her apartment in Foggy Bottom.

Charlie Martin:

Let’s start from the beginning – before you were a young actress in New York, before your career at the newly formed National Endowment for the Arts, and before your long marriage to your late husband, John Clark. You are 85 now and are living in the Chevy Chase House, healing from a broken hip. Take us back to where and when you were born, and who your parents were.

Ana Clark:

I was born on Jan. 18, 1939, in Niagara Falls, NY. My mother was Puerto Rican, and my father was British. Her name was Mercedes Hernandez and he was Sydney Steele. She was Catholic, and he was Protestant. They met at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and fell in love and decided to get married. This is way back when that was unheard of. Neither family was happy with their religious difference and the Puerto Rican and British relationship was out of line in those days. But, they were crazy about each other, and they overcame the negative opinions.

My father had to promise, as an Episcopalian, that when he married his Catholic wife, if they had children, he would raise them Catholic. It almost killed him [laughs]. But he did make that promise because he so loved my mom, and he kept the promise and raised my older sister, Carmen, and my younger brother, Arthur, and myself as Catholics. As he went through that process, he fell in love with the education we were getting and the nuns. He had never even met nuns as far as I know in England, but they were wonderful women, and they were giving us a terrific education. So he became a happy Protestant husband to these Catholic kids and his Catholic wife. It was interesting to grow up in that environment.

What do you remember about Niagara Falls?

We moved before I was old enough to remember it. I only remember my mother telling me a story about Niagara Falls. She was Puerto Rican, unaccustomed to Niagara Falls’ temperatures, snow, ice, etc. But, I remember her story later that she had turned my older sister and myself loose into the front yard, it was winter, and there was quite a lot of snow out there. She was standing at the door, and saw her two little girls go down a few steps and take a few steps and then she realized they had vanished into the snow! She literally couldn’t find them. She told us how she ran down the stairs, climbed through the snow and grabbed her two little girls [laughing]. Of course, I don’t remember that, but it was vivid enough for me to remember that story. And that’s all I know about Niagara Falls, then sometime thereafter my family moved to Wilmington.

What prompted the move to Delaware?

My dad was working for the DuPont Company, and they transferred him from Niagara Falls to Wilmington. Actually, we lived in New Castle, DE, a small town outside of Wilmington. Later, we moved from New Castle into the city of Wilmington, and we lived there for quite a while.

Were you and your siblings very close growing up?

Not really. I mean, she was my sister and he was my brother, of course we were close, but I hear a lot of people talking about their baby brother or big sister—I don’t remember it like that. I just remember having them and that we were family; I don’t remember a favorite or particular sibling, or if I do it was probably my “kid brother.”

How would you say your religious upbringing and Puerto Rican heritage influenced you?

It’s an interesting question. I was raised Catholic and I went to Catholic schools. I think that not only the quality of the education, but the values that the Catholic Church was giving us stayed with me and are still with me. Unfortunately, I didn’t often meet the Puerto Rican side of the family. Our family went to Puerto Rico several times by ship. I was pretty small and didn’t speak or understand Spanish, and learned that there were lots of relatives in Puerto Rico, and they all couldn’t wait to meet us. So it was overwhelming for me because I didn’t get the language but I understood the love, care, and the fun of my Puerto Rican side of the family—I will always remember that. On separate occasions, the Puerto Rican grandparents and the British grandparents visited us in Wilmington. I remember those visits as well. So it’s not as though we were, you know, cut off completely. We were pretty cut off but not totally—there was still that influence. My mother volunteered for a charity group, which she called the Spanish nuns, in downtown Wilmington, doing whatever needed to be done for people who were hungry or didn’t have enough clothing or whatever. That was part of what my mother was doing with the Spanish community in Wilmington. All of that was part of my growing up, part of my learning to be who I am.

Did your mother infuse Puerto Rican culture into the household through cuisine or language or stories?

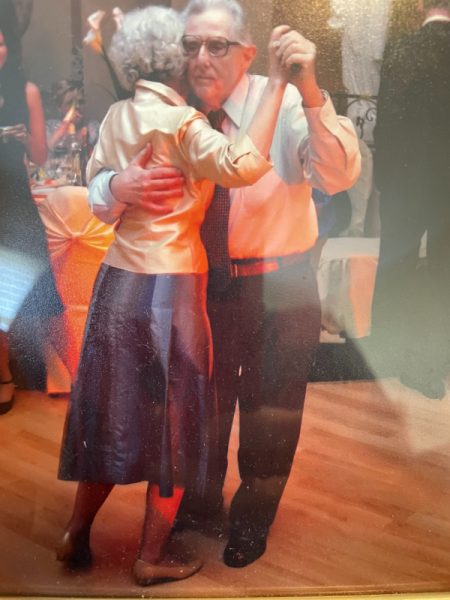

I don’t know how to put this except that basically only the King’s English was spoken in the household, probably because of my dad. I learned some Spanish by listening to my mom talk on the phone to either relatives or the Spanish nuns. I began to pick up some Spanish words, so I know a little when I hear it, and can translate some of what I’m hearing. The cooking, yes, there were rice and beans and those special chicken dishes and the yummy plantains. My mother loved to dance with my dad. I don’t know what it was because I was a kid, but it was a kind of music and movement that was delightful to me. I think it was tango—I really don’t know what I was watching. But I know I loved it. I think that was part of my mother’s influence as well.

Was there a large Puerto Rican or Catholic community in Delaware or New Castle?

Not that I’m aware of no, not Puerto Rican, not Spanish, even. Certainly not in New Castle. But in Wilmington, there was enough of a Spanish community for my mother to be volunteering in downtown Wilmington with the Spanish nuns. So that does suggest that there was Spanish influence in Wilmington, but I was never really exposed to that. That was one of my mom’s activities. I was pretty removed from Puerto Rican culture and even British influences. My dad—God bless him—had decided, I learned this when I was a kid, that he was going to become an American citizen. When he became an American citizen, he decided he was going to lose his British accent, and he did. So if you met him, if you’re a linguist, you might pick up something but not otherwise. Trust me, when I learned that, I was so disappointed! It was like “Daddy, why did you do that? I love the British accent—you don’t have it!” It was because he made up his mind: He became an American citizen. He wanted to sound like an American and so he did.

Tell us about your Catholic education.

As I said, I went to Catholic schools: a parochial school in New Castle, but then quickly into Ursuline Academy which was an all-girls Catholic grammar school and high school in Wilmington. From there, I went to Marywood University (in Scranton, PA) —also Catholic women—where I got my college degree. So my education was all-girls, all-Catholic schools, and my dad was perfectly happy with that.

Did you enjoy the continuous all-girls Catholic environment? Or did you ever want a co-ed environment?

I don’t remember being discontented. But you know it was peculiar. Especially in this day and age like: What! All girls, all your life? Well, it wasn’t totally that because Marywood had the all-boys University of Scranton in the area, and we did programs with them, mostly plays is what I remember doing because I was a drama major and I was going to be an actress. We did some fully staged plays with the boys from the University of Scranton. So it’s not like we didn’t interact with guys – we did but it was, you know, they had their campus, we had our campus, they had their classes, we had our classes. So it was pretty separate.

We understand you graduated from high school at age 15—tell us about that.

My older sister Carmen started school before I did. She would come home from school and tell me what she learned or teach me to start reading or something, so I started a little ahead of the game. I do remember going straight into the first grade in New Castle before we moved into Wilmington. I was given some preliminary tests for first grade. Next thing I knew, Mom and Dad were telling me that they were going to put me in the first grade because the tests showed I would be bored if I went to kindergarten. A little later I skipped first grade and went to the second grade. By then I was at the Ursuline Academy in downtown Wilmington. We had a wonderful tough cookie of a nun, and she had a small class of little people like us. In second grade, I was already a little younger and smaller than most of them. But we really learned, big time, so instead of going to the third grade, I went to the fourth grade. So I had gone from nothing to second grade to fourth grade, at which point I caught up with my older sister. That was pretty hard on her, and it was actually not too good for me. But that’s the way it was from then on and we graduated together. I was 15 and she was probably 17 or 18.

During those early years of school was there ever a time or experience that made you realize that the arts and theater were what you wanted to pursue for a living?

This is a little weird for me, but I seem to remember that when I was little, seven or eight or something, we were in plays at Ursuline. This sounds like ego, but I remember that sometimes in those plays, one of them that I remember, when I had lines and talking parts, I became aware that the audience got really quiet. It was peculiar for a kid my age because I didn’t really know what that meant, but it was like Wow! And I love people—this is a little sidebar, but my mother caught me staring at people several times when I was a kid on the public bus going to downtown Wilmington, and she would tell me, “Ana! Stop staring at people!” I later realized I wasn’t staring – I was a people-oriented kid (and) I watched people. I still do it, even here (in the lobby of the Chevy Chase House). I really enjoy getting to know people or simply getting to know what they look like, what they walk like, what their languages sound like. I didn’t remember that I had been that way since childhood until I remembered now my mother telling me to stop staring.

My interest in the arts starts with that experience as a child – to be able to affect an audience and also to be somebody else—I thought that was fascinating. If they would give me a script and ask me to play a role, I loved that because I loved to sort of crawl inside of somebody else and be somebody else. I don’t really know why, actually. By the time I was in high school, I decided I really was going to be an actress, and then I went to college where I was a drama major and French minor—wasn’t too good at the French (laughing).

When I graduated from Marywood, I went to New York City. As I mentioned, I graduated early because I went through school young – finished high school at 15 and got out of Marywood when I was 19. I went to New York City to be—what did I know! —in the theater. I look back, and I think my mom and dad must have turned gray—you know, having a daughter exposed only to all-girl, all-Catholic schools going to New York City to be in the theater! But they let me do it.

They were amazing parents, my mom and dad. I lived in New York City for probably five, maybe six years. I was not highly successful and very poor, so I went to work looking for jobs just to live. I went to an office temporaries organization where you would sign up and tell them what kind of skills you had or what kind of job you were interested in doing. As a result of that, I ended up working in and for some of the most interesting places in New York City. My favorite one was the Audubon Society, which I absolutely loved. But I also worked at Scholastic Magazine, which was very interesting, and for a French importing company, which was fascinating because I didn’t know anything about importing from abroad to the United States.

I also volunteered at campaigns for Ken Keating and John Lindsay, both Republicans, Keating for senator and Lindsay for mayor. And I also volunteered as a reader at Recording for the Blind.

So I was always active and learning. But that was during the day, and in the evening, I did a couple of off-Broadway shows and also one television program. I was not a member of the union, so I made almost no money. You know, being in the theater and being on television didn’t mean I was making a living, trust me—it was like $10 a week because getting into the union was very hard back then.

Tell us more about those off-Broadway productions and the television show.

The television show was called The Nurses, and I was an extra and had to be there really early in the morning. I was also a stand-in for the two lead members that were an older nurse and a younger nurse; they found me close enough physically that if something happened, I could step into the role of the younger nurse. The extra role meant that I was in crowd scenes, and the only scene I remember was standing behind a cash register—which I had no idea how to work—checking out the nurses. I remember once they told me I had to do a stand-in because the gal I was the under-study for was sick, and I was terrified. I only had a few lines, and they didn’t shoot me full on, so nobody could tell that it wasn’t the gal. That was my limited experience with television; it was very interesting.

For my theater experiences, one of them was a revival off-Broadway of the Arthur Miller play called The Crucible, which is fabulous. The show was a translation of the McCarthy hearings which were going on in Washington, where individuals suspected of being communists were being prosecuted all over the place, and peoples’ lives were ruined because of manic beliefs. Arthur Miller put that situation into the town of Salem, MA, where prosecution of people suspected of being witches had run rampant. There were good, normal people, and there were manic people—I guess they’d be called extreme right wingers now—that were looking for witches. I was playing a servant girl, and one of the couples I worked for was accused of being witches. I was asked to accuse the couple to join in their prosecution. The couple ended up being hanged. Arthur Miller did an extraordinary job. For me, the play was so powerful, and I was working with really professional actors, actresses, and director for the first time; it was a big step for me. I think that I got paid $10 a week, and we did seven performances a week.

There were performances most weeknights with matinees and evening performances on Saturdays and matinees on Sundays. It was a lot. During the day, I would go back to the Audubon Society or other part time jobs trying to earn a little bit more money. And the other thing I did off Broadway was a play by Ionesco called The Lesson. It was really weird; I don’t recommend (it). It had a two- person cast – a professor and the student – I was the student. It was sort of a spooky play—I think the professor ended up killing the girl. Anyway, it was weird. I remember things that I was supposed to do as the student, including develop a toothache while learning from him. The toothache kept getting worse and worse, so I had to learn how to speak with increasing pain and difficulty. I’ll give you a PS on that one, which is that my dad came to see me in the play, and when we got together the next day he said, “You know dear, I went to my hotel room and I developed a toothache and I couldn’t stop it!” I felt sorry for him, but I was happy—I thought I’m not a bad actress; I’m doing a good job! Those are the two experiences that I remember from working in New York theater. I also remember living in very modest circumstances.

What was the process for auditioning for all these different shows?

There was a newspaper called Backstage and another one called Variety, and sometimes they would put casting calls for different shows. I would try to follow up with them with really limited success. I had also done some professional summer stock theater when I was in Wilmington in high school. A (fellow summer stock) actor remembered me and when they were casting to replace somebody in The Crucible, he remembered me and gave me a call—I thought: Why? I almost couldn’t remember his name! That’s how I got to audition and secure a role in that play. I don’t remember the audition for the student role in the Ionesco play. Basically you could look in the newspapers, you could do work somewhere and somebody would remember you and call, or you could just hang around theaters and see if anybody needed anything—that wasn’t very useful.

Given how competitive acting was in the ’60s late and ’50s, and the fact that you had to manage multiple part time jobs, did you ever feel stressed or a bit discouraged in New York?

I did, but, you know, I really loved it, and I thought I could do it. I guess I’m sort of an optimist or at least upbeat because if I had to do those part-time jobs, I would find them interesting. I never got like poor me poor me! I just didn’t want to live that way. Ultimately, my older sister moved to New York and got a job with Time Inc., the Time Magazine company, and she moved into the local YWCA, and then I moved into the YWCA. So there we were in the middle of midtown Manhattan in the YWCA, which cost relatively little. It was good to have family and friends, so I got through it fine.

There was a point where I said to myself, you know what Ana, the theater in New York does not need you, so move on! I decided I was going to leave, and my mom was a little ill, so I went home to help take care of her. In the meantime, my father, who was my press agent – that’s what my mother called him – had read in the New York Times about the creation of a new government agency called the National Endowment for the Arts.

He told me I should go get a job there in Washington, and I said okay, so I started sending resumes, resumes, and resumes. There were only like four people in that office, so they were drowning in paper down there. I got on the phone and couldn’t get through. Once I got the phone number, it just rang because they didn’t have the answering machines like they do now—it was a big struggle. Then, somebody answered the phone one day, which shocked me and I – boom! – said “I’m going to be on the train tomorrow from Wilmington to Washington, and I’m going to come because I want to be interviewed for a job.” The person said, “All right, hon.” I got on the train the next morning, just crazy, got off the train at Union Station and realized I didn’t know where I was going. The lady had said to come to the Old Executive Office Building, which is where the agency was because it wasn’t a full agency yet. So I got into a taxi and said, “I want to go to the Old Executive Office Building,” thinking to myself this cabdriver better know where it is, otherwise, we’re dead! But he did. It was a beautiful building right next to the White House. I thought, THAT building is the National Endowment for the Arts? Anyway, I went in, and the guards cleared me and told me to go to the second floor, and I was like Wow! I went up to the second floor, and they told me room dadada, so I’m walking down the hall, and there’s a big circular sign up against one of the walls on the left side, and it read the Vice President of the United States. I thought, wait a minute—I’m in the wrong building – what is this? (laughing). But I went into the specified office, and there was a secretary and a little office behind that with piles and piles of paper and phones ringing. It was chaos. When I was being interviewed by the secretary she stood up, looked over my shoulder, and I turned around and there was this big, bald, grumpy looking guy who was Roger Stevens – the chairman of the Endowment and the founding father of the Kennedy Center! Standing next to him was Gregory Peck! Of course, somebody my age saw Gregory Peck in person this close, I almost fainted because he was gorgeous and a big movie star! The secretary interviewing me said to the two of them, “Oh this is—what did you say your name was hon, Ana Steele? This is Ana Steele; she’s been on Broadway,” and I’m saying “No, no, no, not ON Broadway, OFF-Broadway! She was trying to sell me to them, and I was embarrassed because she was overdoing it. They didn’t really pay a whole lot of attention, but I ended up with a job as a clerk/typist. I didn’t know how to do shorthand, but I could fake it because I pretended to do it when I was doing office temp work. You could pretend that you took shorthand, and it worked. When I got tested in Washington, I did the same thing, knowing that I was going to flunk, but I passed, and it was like ridiculous. I got the job at the Endowment in 1965 when I was 26.

Before we get further into life on the staff of the National Endowment for the Arts, can you tell us what the agency does?

The National Endowment for the Arts was signed into law in 1965 by President Lyndon Johnson. It is a federal agency that provides funding to foster the excellence, diversity, and vitality of the arts in the United States. He called it a part of the “Great Society” to encourage artistic expression. Grants are given to nonprofit arts organizations, individual artists, state arts agencies, and regional arts organizations. The chairman of the NEA makes final grant decisions based on recommendations of advisory panels made up of experts in individual artistic fields from all over the country. The National Council on the Arts, an advisory board to the Chairman of the NEA, whose members are appointed by the President of the United States, advises on policy issues and makes final recommendations on grants. At least that was the way it worked when I was there.

So you were a young woman trying, but not quite succeeding, to be an actress and the next thing you know you are working at the federal agency tasked with supporting young artists like yourself. What was the career jump like – nerve wracking or scary?

No, actually, since I was hired at the lowest grade as a clerk/typist doing the same kind of work that I had been doing in New York, thank God. I mean, there were very few of us in the NEA’s early life, maybe seven or eight people in the whole agency, which was just getting born. But I was just so happy to be in a place that was going to encourage the arts in this country. I just found that overwhelming and beautiful. So I didn’t mind being a clerk/typist – I thought, I’ll do whatever I have to do. It sounds goofy, but I was a happy camper, I really was. I did progress over time in the agency a lot. I got bigger jobs, and the pay was better over time.

Do tell.

At some point, for reasons I will never quite understand, I became director of budget—moi? But, you know, you just do it, and thank God I could. Then, I was director of planning, and then director of planning and budget, then program coordination. Eventually I was deputy chairman, for a while, and later the then-chairman left and the Clinton Administration hadn’t found a replacement yet, so they asked me to be acting chairman. I said no and told them why, but then they came back and said, “You’ve got to do this. Everybody says you’ve been there from the beginning—you’re the only one who knows everything.” They quickly found a new chairman, though – Jane Alexander, who’s a fabulous actress. She made me her deputy, and boy was that heaven. She was—and is—a unique human being.

I also met my husband at the Endowment. Nancy Hanks was chairman then and she hired him. She was a Nixon appointee, Republican, and she was splendid too. That was a message that guided us all, which was that we were a non-partisan, bi-partisan agency that had nothing to do with politics. Program deputies hired were experts in music, dance, theater, creative writing, visual and media arts and all that. I look back and think my goodness! It was a blessing that we lived that way! Sometimes it was hard—we had problems with the Congress when they would come after us for doing things they didn’t approve of. It was a magic agency also because I met (my husband) John.

Which NEA projects, in particular, stood out to you, like Westbeth Artists’ Housing in 1969 or the Dance Touring Program, from around 1968/69, for instance?

Those are two super projects that you mentioned because they were huge and had great impacts, especially on dance touring which put dance on the map all around the country. Professional dance had been primarily in New York and a few other cities, and we helped put companies on tour nationwide – rewarding for dancers, dance companies, and their growing audiences.

Tell us about your early years at the NEA under Roger Stevens.

We had space in the building that housed the National Science Foundation, and we had a few offices in that space. It was a very small staff, and Roger Stevens was hiring the directors for a lot of programs, so over time we built up until we were 15 or 20 people. We all worked very closely together, and he was the perfect chairman, although he was mumbly and not very outgoing, but we all loved him because he was just right for the job. He would go up to Congress when we got in trouble for doing something thought to be inappropriate, and he would bumble on up to the Congress and some probably thought, here comes this big bald, grumpy looking guy. He was also a real estate magnate and Broadway producer, and they didn’t know what to make of him. They were expecting a weirdo, but he would take care of everything with them in an hour meeting, and everything would settle right back down again. He was brilliant at his job, and he was also putting together the Kennedy Center in his spare time. He took no salary as Arts Endowment Chairman.

I remember when he left to go full time to the Kennedy Center, the secretary was going through the materials in his desk, and in the top drawer they found a letter from Jacqueline Kennedy thanking him for his work—he didn’t even take it with him. He just did the work. He never looked for thanks, praise, or even acknowledgment for himself. But imagine! A letter from Jackie Kennedy, and he didn’t take it with him! He was brilliant and totally self-effacing.

When you say the NEA “got in trouble,” I assume you are referring to controversies in the 1980s and ’90s with the American Family Association trying to shut the Endowment down, and President Reagan’s failed attempt to abolish the agency in 1980. Later, there was (Andres) Serrano’s “Piss Christ” and (Robert) Mapplethorpe’s sadomasochistic portraits, just to name a couple, that drew press attention and embroiled the NEA in controversy. What was that like to live through? Were staff members discouraged, or did these controversies motivate them to work harder?

The latter. We were not discourageable, but we were very upset, especially with the American Family Association. They were up in Congress, up in the press, telling stories about us to make us sound so utterly appalling. They would muster their forces to attack things that they found inadequate or improper for the government to assist. They would go to the press and tell their stories and do their mega-mailings all over the country to their members, who would then bombard the Congress with mail. It was tough.

After Roger Stevens, Nancy Hanks became chairman in 1968. Did the agency’s culture change?

Somewhat, yes, partly because we kept growing. Nancy was a whiz-bang and charming lady. I’d never met anybody as smart as Nancy. She persuaded the Congress to increase our budget and she hired more people. It was heaven: We just grew and worked hard and did good work. She was a terrific chairman; nobody had any feelings about Oh, Roger was a Democrat—L.B.J. had signed the legislation— and here comes Nancy Hanks hired by Nixon. Nancy was wonderful. We ended up being good friends as well.

How did the Endowment decide which artists and organizations got funding?

We had a system of advisory panels made up of experts in each of those artistic fields from all over the country, who would come to Washington for a day or a week, depending on how many applications were landing in our agency. We didn’t want government bureaucrats making those decisions. We wanted people from the arts fields to make recommendations; while they would not make final decisions, their recommendations would be honored. These advisory panelists, who worked in the various art genres and fields, would go through all the applications and make recommendations about funding. The next step was to take those recommendations to the National Council on the Arts, the advisory body appointed by the president of the United States. They also represented all the different fields and viewpoints. The panel recommendations would go to the National Council, whose recommendations would go to the Chairman for final action.

You became the NEA acting chairwoman in 1993—what was that job like? It must have been enormously stressful.

We were under attack big time when I was acting chairman, and that was really hard. I had to testify before Congress; the staff was on edge. We were all on edge because our budget was cut almost in half. It was hard, but we so loved what we did. We didn’t have people quitting. We didn’t have people going to the press complaining. We just hung together and did everything that we could as best we could. My favorite moment – except for when I had staff meetings with everybody, which I loved because I loved all of them – was when we were under fire, and I was sitting in the chairman’s office, and I received a phone call. When I picked it up, it was Mary Bain, the lead administrative assistant to Congressman Sidney Yates, a Democrat from Chicago, who was a big fan of the Arts Endowment. He chaired the appropriations subcommittee, which gave us money. He loved the arets abnd he had fallen in love with our programs and the program directors. He was a great friend and supporter. I pick up the phone and hear, “Hi hon,” “Who’s this? “Mary” “Mary Bain?” “Yeah hon. I’m just calling to tell you that Sidney Yates said keep your little fanny right in that chair!” Maybe it wasn’t quite as graphic, but it was powerful. I laughed and almost cried because I was so grateful for that kind of support coming from such good people in the Congress. You know, it meant so much to me and still does. Boy, there’s some wonderful people in my life and in the history of the arts in America.

Tell us about some of the people you’ve met and connected with through the NEA.

I can’t even begin. I mean, the members of the National Council on the Arts, the presidential appointees, way back in the very beginning like Leonard Bernstein, Isaac Stern, and Jerome Robbins, Harper Lee—the writer of To Kill a Mockingbird – and John Steinbeck. Later, people like Toni Morison, Helen Frankenrhaler, Jacob Lawrence, choreographer Martha Graham, actor Sidney Poitier, and jazz artist Billy Taylor. I’m sorry, I just go blank. If I could go back to my apartment in Foggy Bottom, I have a lot of wonderful lists of Council members over the years—you’d all fall over! The members would rotate every four years, so we had change all the time; we had old guys and new guys all the time. We tried to keep our heads because they were presidential appointees. We couldn’t appoint them, all we could do was advise the White House who might be a good replacement for somebody, and they would do whatever they wanted to do. But, yeah, there were some extraordinary people, especially in the early days.

Speaking of people, you met your husband, John Hunter Clark, while at the NEA when you two were colleagues. I understand you were married for 42 years until his death at age 93 in April 2021. According to his obituary he was a graduate of Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School and was devoted to the arts, including being an author, lyricist, and director of his own comedic adaptations of popular musicals of the day. You worked directly with him?

I met John when Nancy Hanks was chairman, and he was working for her. She was looking for more staff because we were growing. She was good with the Congress. She was Republican, which helped with Republican groups that didn’t love us. Anyway, John had worked for the Pentagon, then the Office of Management and Budget, then the Poverty Program, running the Office of Economic Opportunity Community Action program. He was very involved in that and saw the writing on the wall when Nixon was elected. He figured that the Poverty Program would be put out of business, since it was not much valued by most Republicans. John started looking for another job before they shut the whole place down, and he read about this new thing called the National Endowment for the Arts. He had heard about it and was interested because he loved the arts, especially music. He was looking for a job and called his big brother, Jim, and said, “Jim, do you know anything about this? Because I’m thinking of looking for a job there. I know it sounds a little far fetched.” His brother said, “Oh, yeah, the chairman is Nancy Hanks, and we used to date.” (laughing). Jim had been married to someone else for eons, so it had nothing to do with anything, but John told him, “I’m not gonna call up and say I’m Jim Clark’s brother!” He said, “Go ahead; it can’t do any harm.” So John met Nancy for an interview and mentioned that in passing—it was not much of a credential. She hired him to be special assistant to the chairman.

He later told me that he had gone to the government organizational manual, which used to print information about all the big-time jobs across the federal government, and he saw that the NEA director of planning was a woman named Ana Steele, and said to himself, “Oh my God, first of all, she’s planning, and I was planning at OEO [Office of Economic Opportunity], so that’s not going to work because they can’t have two of them. And the name Ana Steele conveyed to him a large Germanic woman with power! After he was hired, Nancy brought him in to meet me, and – in his words – he saw a little young thing sitting in a chair with her shoes kicked off, sitting on her feet with a cardigan sweater thrown across her shoulders—he was like, Whoa! this is not even close to what I imagined!

We worked together literally for six years as co-workers [before marriage]. Nancy was a workaholic, and he was her special assistant, and I was probably her next closest, so we all worked late every night. Nancy would finally go home, and then John and I would walk home. He lived in Georgetown, and I lived in Foggy Bottom, so we would walk home together a lot. At some point it would be, you know, John would say, Are you hungry? and I would say, I’m starving! Then we would go to eat dinner somewhere. John’s favorite way to describe our relationship was an “impetuous whirlwind six-year courtship.” We got married after that impetuous-whirlwind-six-year courtship—that’s the truth, except the whirlwind courtship is sort of a joke. Neither John nor I would be able to answer if asked if there was a moment that we said to ourselves, I’m in love! We just grew into love. I remember one day saying to myself, I can’t imagine my life without him. I guess that’s falling in love. It was beautiful – what a blessing.

Long before you and John moved into the Potomac Plaza Cooperative Apartments in Foggy Bottom where you spent most of your married life, you, Ana, lived in Dupont Circle. I understand there were a lot of social movements in that area at the time—were you involved in these movements?

I was not—I remember that when I first came to Washington in ’65, I was on P street, a few blocks off Dupont Circle, which was a hotbed of all kinds of demonstrations, especially against the Vietnam War. I remember walking out of my front door one day, and I saw police with clubs beating kids down to the ground. I had never seen anything like that—I was horrified. I didn’t ever do anything in any of those movements except support them. I had some interesting interaction later with members of the gay rights community in Washington, and did something supportive with them—I can’t remember exactly what.

Also while at Dupont Circle, I volunteered tutoring a young African American in a program called, “Future for Jimmy.” My young student, William, was very special. I remember him still.

Because you and John had a love of the arts in common, and when married lived not far from the Kennedy Center and other entertainment venues, did your lives apart from work involve the arts?

Yes, absolutely. Music was John’s passion, but so was everything in the arts – like it is for me. Whenever we could afford it, John and I went to everything possible. We took a subscription to the dance, but we went to everything else when we could. We both loved all of the arts and having many of them right there too. That’s one of the things now when I’m trying to decide whether to go back home to our apartment or stay here [in the Chevy Chase House, where she gets regular physical therapy after breaking her hip more than a year ago]. I have a friend – she and I are subscribers to the dance series – so she’ll come and pick me up and take me down there, hobbling around. John was really fading in his last years, but we would keep going to the Kennedy Center, and they gave him seats in the aisle for the handicapped. I’ve kept that seat because as it turns out I’m handicapped now. I use a walker.

It must have been difficult to retire from a career that was so focused on the arts, something you loved. You retired in 1998 after 36 years with the NEA.

It was very hard. We had new leadership, and the agency was changing. It didn’t feel the way it did before. I don’t remember even what I was doing then, probably deputy for programs or something, but I just felt we weren’t the passionate arts people in the way we had been. Of course, I had worked there a very long time, and was of an age to retire, and my husband had retired. He was 12 years older than me. One day, we were driving home and John listened to me and said, You know, sweet love, you may get to the point where you don’t really love going to work anymore. Think about that. I decided that I was going to leave. I had a huge farewell party, which was amazing. Congressman Yates came, which was a big wow because everyone told me he doesn’t go to retirement parties. The fun part was that I had become notorious for editing, and we had these colored pens, and mine was purple; everybody started to call me the “purple pen lady.” For my farewell party, they had decorated everything in purple! I had not been let in on any of the plans for this farewell party, so, trust me when I walked in I was like Wow! There were like 100 people there—most of the staff—and then when I saw Sidney Yates, I almost fainted [laughing]. I loved them, I loved my staff, I loved the people, I loved the work, I loved my sweet angel, John. I’ve had too blessed a life, I don’t know how that happens but I’m so grateful.

And what has life after retirement held?

My life was really full. I didn’t need to do anything new. We had joined the Foggy Bottom West End Village. The Villages are all over the world now. They are community-organized groups that get together and decide what they might do to be helpful for the neighborhoods or areas in which they reside. I did some projects with them and for them, which was really good. I enjoyed that a lot.

Church is still a part of my life. I go to the St. Stephen Martyr Catholic Church [in Foggy Bottom]. It’s a beautiful small church. I’ve been going there ever since I can remember. When I was living off of Dupont Circle, I was probably going to St. Matthew’s Cathedral, but then I came to St. Stephen’s. They have an exquisite choir and, at the moment, a wonderful pastor, Monsignor Paul [Dudziak]. The other priests are also wonderful like Father [Klaus] Sirianni.

The church is poverty-stricken, and there are concerns that it may be shut down. Sometimes when you call the church, whoever answers the phone might be the priest because they don’t have enough regular volunteer people to come in and do secretarial work. Anyway, I had never been in the back of my church until I went back to go to Mass a month or two ago. I got there when the 10 o’clock Mass was finished, and the 11 o’clock wasn’t starting, so I got myself into the back of the church and just sat in the back of the church. I could see the whole church—it’s gorgeous, absolutely beautiful. I was so happy that I was early because I had a new vision of the whole church.

Tell us about your travels with your husband. We understand you cashed in on all those arts contacts you made while working at the NEA and got to see the fruits of your labor – arts in action all over the United States.

My sweet husband had said, You know, everybody retires, and they want to go to Europe. Why would people go to Europe? We have this big, beautiful country, and nobody’s seen it, including us. So we decided to chop the country in half, and we went one year to the southern part and the other year to the northern part. John was the man with the maps and the travel books, and I was the woman on the phone calling all those people we had met over the years – panel members and council members and artists. Before, they would all say to either John or me, When are you going to come see my museum? When are you going to come to see my folk arts program? When are you going to see my dance? John assigned me to pick up the phone and say, Hi, remember me? You were always asking when are we coming – we’re coming! Our rule number one is we’re staying in a motel because we aren’t moving in on anybody, and we will only be there probably a day or two but we’d love to see you! We had the best trip. Before we left, friends were saying, Are you kidding? You’re gonna get in the car, drive across the country, and then you’re gonna do it again? You’re gonna end up divorced. You can’t sit in the front seat of a car with anybody and drive 24 hours a day practically without somebody starting an argument. Never happened. We were cool. It was wonderful, and we loved it. The country and its sites are exquisite.

Give us just one magical moment of the trip.

The one that immediately comes to mind is when we were in Arizona going to the Grand Canyon. We were driving toward it and we saw a lot of cars were pulled over to one side, and John wanted to see what it was about. We parked the car, walked over there, and it was the sun setting on the canyon across the stone—I’ve never seen anything like those colors, and I can still see it – it was exquisite, and I’ll never forget it. I’m sure John took a lot of pictures. I told somebody to count them in my apartment and we have 83 photograph albums covering most of our lives.

What went into the decision to move from your apartment, which is close to all the things you love, to across town into an assisted-living facility?

Two years after my husband died, I fell and broke my hip in our apartment. I went from the hospital to a place called Forest Hills and then from there to here at Chevy Chase House because I still can’t get around by myself. I was in so much pain, and I know they were giving me all kinds of pain medication. When I came here, the biggest blessing about being here was physical therapy. They have therapists here, occupational and physical, and they do magic.

I miss [my apartment]. What I mean is that it’s very different. One plus side here is – and it’s a big plus – meals that I don’t need to cook myself. The staff by and large is really wonderful, skilled, warm, and caring. And I have made a lot of friends because of sitting in the lobby and staring—you know, you get to know people! That’s a big blessing to being here; I feel as though everything surrounding me has been a blessing more than a downside. I’m not especially crazy about the room I’m in. I live in a studio, and I’ve been here for well over a year and it’s getting crowded in there. I have only one chair and the bed. I have a walker and a wheelchair. You can hardly move around in my room [laughing]. But I’m blessed to be here, and I’ve met some really interesting people. When I’m trying to make up my mind to stay here or go back home, I talk to a friend who lives in my old building [Potomac Plaza], and once she said, I’ve lived in this building for more than 24 years and I haven’t made many close friends. There are so few situations that lead to making friends (in a condo building) – you don’t eat together, there are no programs together; we have only an annual Christmas party when everybody’s in the lobby and says hi and that’s about it. On the Fourth of July, they’re all hoping for enough space on the roof for the fireworks. She told me to think about it.

I have a niece who called me a couple of days ago. She’s very smart, and she was telling me that studies of seniors make certain issues and points about what makes people live longer and happier, and I said okay whaat, and high on the list was “friends and collegial activity.” It’s good for health, it’s good for the brain, it’s good for everything. It’s very hard for me to give up my Foggy Bottom apartment. I mean, my life was there. But this is really important to me now, so I’m still struggling with my decision.

What would compel you to return to Foggy Bottom?

The neighborhood is beautiful, it really is wonderful. It’s near the Potomac River, and everything is walkable – walk to church, walk to the river, walk to Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods, walk to the Kennedy Center, walk to the Tazza Cafe. All of those things are important to me—being able to reach them and involve myself in them. I have to make up my mind. I’ve only twice been back to the apartment where John died [since my fall]. It was John’s niece who said, Come on, everybody’s overthinking taking you in there, including you Ana! We’re just gonna do it, and we did. I didn’t go into the room where he passed away, but I spent some time there. It felt better than I thought it was going to feel—I thought I was going to fall apart, but I didn’t. I’m leaning towards staying here at Chevy Chase House, but I still don’t know.

Your life is so inspiring, especially your work in the Endowment. Could you give a word of advice to young people who want to pursue a big job or interest but don’t know where to start?

I think probably the most important thing is to pick an organization or agency that has a mission or subject you personally identify with or care about and go check them out to see whether they would help enlarge your interest or even shift you from something that you feel strongly about. Stick with your core and don’t think about politics or money or anything for a while. Think, “what do I care about, what means something to me, what do I want to spend part of my life involved in?” This sounds selfish, but it’s actually selfless if you think about it.

Was there anything that we haven’t covered that you’d like us to ask about?

No, I just wish I could show you some of the pictures from my apartment—I have some wonderful pictures of me and John.

END

Copyright Historic Chevy Chase DC

Oral history interviews may be copied for personal, research and/or educational purposes only under the fair use provisions of US Copyright Law. Oral histories accessed through this web site are the property of Historic Chevy Chase DC. the copyright owner.

Use of these interviews is subject to the following terms and conditions:

- Material may not be used for commercial purposes. Short quotes and references are permitted for instructional and publication purposes.

- Users must provide complete citation referencing the speaker, the interviewer, the date and website with URL address.

- Users may not re-post or link the oral history site or any parts of it to another program or listing without permission.

Questions about the use of these oral history materials and requests for permission should be directed to hccdc@comcast.net or HCCDC, PO Box 6292, Washington, D.C. 20015-0292.

: